Explore Feuilletons

Awakening

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Keywords

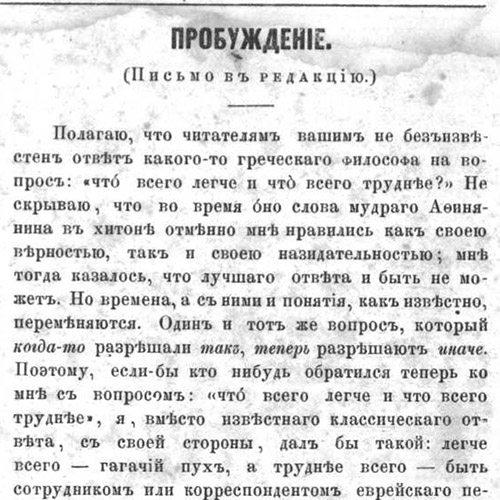

Original Text

Translation

Lev Levanda, “Awakening,” 1861. Translated by Conor Daly

I take it that your readers are not unfamiliar with the answer of a particular Greek philosopher to the question “what is the easiest thing in the world and what is the hardest?” I won’t deny that at one time I was full of admiration for the response which that wise old Athenian in his chiton came up with – for its truthfulness and also for its educational value; back then I thought that it would be impossible to come up with a better answer. But, as is well known, times do change and our understanding changes along with them. The very same problem which was solved one way then is solved another way now. So if anyone were to ask me now “what is the easiest thing in the world and what is the hardest?” instead of giving the classic answer I would answer as follows: “The easiest thing – by which I mean the least burdensome or lightest thing – is eiderdown and the hardest thing is to be an employee or a staff writer in any Jewish current affairs journal.”

Read Full

Yes indeed, dear readers: when we take into account the ingrained hostility most of our countrymen feel towards the increasing openness in our society along with their predisposition to those extravagant plaudits which appear from time to time… I don’t need to tell you where; and when we take into account that sensitivity of theirs, honed by the sufferings of the ages – a sensitivity which can become excruciatingly irritating – along with the casual, almost patriarchal way in which brother treats brother – yes, taking all this into account, the position of employee or staff writer in a Jewish journal is much more delicate, I would even say more dangerous – it is, in a nutshell, much more difficult than some people might think.

Whenever they expand on some contemporary idea, staff writers end up being accused of dangerous rationalism and even atheism; whenever journalists write about some controversy which is only crying out to be aired in the court of public opinion, they find themselves under the strong suspicion of hating their own people.

What can we do in this situation? What can we do, I ask you? Not everyone is able to prattle away producing constant streams of rubbish – particularly not someone whose motive as a writer is to do some public good, rather than just to have fun.

What good is it, for example, if we in our role as journalists limit ourselves to stating that our town has a Talmud Torah school, a hospital, an anti-poverty charity, and other establishments like those ones? What instruction, what value can our own community or the Jewish communities of other towns possibly extract from such dry, official reportage? But if when we report about our public institutions we also point out the good order and sound management which we observe in a particular establishment – or the absence of those same qualities – and if we uncover deficiencies in how they are run, or list strengths which they might easily acquire, then we can hope that our lifeless printed words will inspire living thoughts in the minds of those who treasure the public good in their hearts; and that these same living thoughts will in turn lead to an even more vital cycle of activity, change, improvement, and transformation. For, if I am not mistaken, the improvement of our public institutions is something almost every Jewish person aspires to. I say every because I think you would need to be someone of very limited intellectual ability – either that or apathetic at heart – not to be convinced that our various public institutions are languishing at present in a state of repair – or should I say of disrepair – which is tantamount to obsolescence and that the practical value they bring our people is doubtful – if, indeed, they are not actually doing us harm.

We must not forget that, with respect to those everyday social functions which encompass almost all of our public administration, our people is effectively self-reliant. Our particular national institutions, very many indeed of them, may count on benevolent approval and external patronage – a patronage to which they are admittedly indifferent. But we still have no proper representative body (Vorstand) in our societies capable of taking on the responsibility of initiating activities for the common good. So who can regulate, guard, observe and pass judgement on the manifestation and functioning of our public interests except an impartial public opinion, one which cannot be bought off, one which is delivered in the form of transparent public disclosure or free speech? This kind of free speech – and we are speaking from experience here – has a more direct effect on our impressionable people than on any other. But this free speech, which is fated to become our supreme judicial authority today, the sole medicine to combat carefully concealed malign intent, the sole remedy for abuse and the whole plethora of social ills which hold our people back from flourishing, prospering, and developing correctly – this free speech, I declare, is having its citizens’ rights denied it by many of our own brethren – whether out of narrowness of vision or for other reasons which we can only guess at – brethren who hunt it down in word and in deed. And that is a pity. Yes, it’s a great pity…

After reading the above lines, readers will think that I am about to go and write some kind of exposure piece – which is absolutely the last thing I have in mind, right now at any rate. You see, I mention free speech here in recognition of its first anniversary on Russian-Jewish soil, and as I turn over in my mind everything that it has managed to achieve for our people over such a brief period of time I feel in my heart such a fullness of warm feelings that I cannot but resort to a few heartfelt words to honor the day when it first came into existence.

One year has passed since that memorable 27th day of May on which we, Russian Jews, hitherto forever silent, for the first time declared to the world our existence as a people ready to make the journey towards our own material and moral awakening, towards progress and modernity. One year has passed since the day when we stopped being perceived by our fellow countrymen as an inorganic mass, a dumb slab, a huge but pitiful chunk taken from some unusual, quite beautiful, but long since dilapidated building, whose original elements, removed from their foundations, cast aside, scattered and dispersed around the world in all directions, have experienced the most diverse fates – fates which are almost diametrically opposed.

Some people deck out their backyard with those elements, fully convinced that they could never deserve anything different, anything cleaner; other people incorporate them into the foundation walls of newly constructed public buildings, in the belief that this chemical mingling of elements will make those social structures even more stable; and still other people use them to mold exotic shapes to decorate the cornices of tsarist palaces thinking that this is fully in line with the spirit, taste, and requirements of modern art.

We will allow unbiased thinkers to draw their own conclusions about these intriguing affairs and will turn now to our proper subject matter.

As we were saying: a year has passed since the date when we ceased to be a dumb slab, because on that date we were given a voice, we started to speak out in public, we acquired a tool which we can use to tell anyone who is minded to listen exactly how we are feeling, what it is that makes us happy, what gives us cause for regret, what evokes in our hearts the liveliest empathy and what we pass by with a quiet, barely audible whisper, exiling ourselves to that old school of sufferance – a school which our people has attending assiduously for many a year now. In short we proclaimed ourselves to be a nation not just inspired by antediluvian concepts but in tune with almost everything which deserves the sympathy of a person and a citizen – a nation determined not to stray by as much as an inch from the spirit of our times, unless we encounter obstruction from circumstances totally outside of our control.

We doubt that anyone who is interested in the moral development of the whole human race will be indifferent to the highly significant fact that a people which had hitherto always been thought of as entrenched in its own ignorance, and pursuing only material benefits, has suddenly, almost without any external encouragement, come up with this idea – to have its own organ to publicly address its own most important interests and issues, its own social requirements and needs. This wonderful idea, long cherished in the minds of the progressive members of our people, has been brought to life. Rassvet [Dawn] has appeared, and with it freedom of speech in the full meaning of that term. Contrary to the well-known proverb chaque oiseau trouve son nid beau1, we looked around us and discovered that unfortunately our own nest was terribly ugly and that not only were we unafraid to share this sad discovery with the foreign public around us – from whom, to be quite frank, we could not expect any particular sympathy – but in a despairing gesture of self-sacrifice we revealed our weaknesses, our national afflictions, and invited anyone to cure them who saw fit to do so. Who can deny that such a conscious process of awakening, such magnanimous self-incrimination offers the clearest proof that our desire to move forward is sincere?

Yes, we have awakened. We were asleep for a long time, and we slept soundly, because the sky outside was gloomy, the kind of weather that just makes you want to go to bed. But may God preserve even our worst enemy from the nightmares which afflicted us – the very thought of them is enough to make one’s hair stand on end and goosebumps quiver across one’s skin. It used to be that a person would suddenly wake up, rub his eyes, fling himself out of his uncomfortable bed and walk over to the doors and windows, just to breathe in some fresh air and lighten the feeling in his chest; but – alas! – would find those doors and windows nailed firmly shut – because there was no way out; and nothing else to do but gasp for air along with everybody else in that dark, cramped, stuffy, and smoke-filled little hut. And so this person, now wide-awake, would wander about for a while and would try and pester one or other of his companions by calling out to them – but no response would ever come back. Clearly it wasn’t yet time to get up. And the wretch would give up in disgust and would reluctantly fall back into a torpid sleep – waiting for that time when the universal awakening would occur.

And lo that morning did arrive! The shout Barkoi!!2 echoed over the whole camp of Israel, like a cannon at dawn. All those people who had a sensitive heart in their chest and a sound head on their shoulders responded with delight to that precious rallying cry and rose to their feet. There commenced the celebration of a sacred rite, a rite such as had taken place in the temple of ancient Sion on the great day of propitiation. Many people became agitated and were thrown into a panic, hearing what sounded like the choir of some new priesthood of Aaron confessing out loud the sins of the house of Israel; but there were many others too who, realizing that this choir was working in the service of their own people, were filled with happiness and joy: “Blessed are our eyes, we who have seen this.” The morning has come at last! Do you hear me, brothers? Sleepers, awake; dreamers, rouse yourselves! The night watchmen, one by one, are leaving their posts. In the guardhouse music and drums are welcoming in the dawn – can’t you hear the sound? The morning bells are about to start chiming and the people will soon go outdoors; maybe the doors of our own little house will open too and we too will hurry off to the great feast day of our kind mother – may she live to delight her sons and her stepsons!... And you, new priests of Aaron, the instruments of our nation in Russia, sound the bells, awaken our people – may old and young alike arise and march forward towards that heavenly light.

We know when God’s day dawns no ills can it conceal… But we have struggled through! By no means all is lost… We’ll lash the masts, we’ll stretch our sails out long, With merest whispers indolence suppress, And on we’ll go, buoyed onwards by this song: O Lord, this coming day we pray you bless!3

Vilnius, May 27 1861 L. Levanda

Commentary

Lev Levanda, “Awakening,” 1861. Commentary by Brian Horowitz

The feuilleton could have its Jewish expression in the Russian language only after 1860, when Osip Rabinovitch issued Rassvet, the first Jewish newspaper in Russian. Rassvet (Dawn) seems to have had two intersecting but contradictory motives. Rabinovitch apparently wanted to give Jews the opportunity to exalt Jewish life for both Jewish and non-Jewish readers. However, he also provided a sounding board for criticism of Jews, even hard-hitting criticism. Although Rabinovitch wasn’t sure which of the two would win out, it was the latter; ultimately, the paper often featured critical voices on Russian-Jewish life.

Lev Levanda (1835-1888), the writer of this feuilleton, was one of the most important Jewish writers in nineteenth century Russia. Among his many novels, the influential Hot Times (Goriachee vremia, 1873) stands out, in which he depicted Jews in the region between Poland and Russia at the time of the Polish uprising of 1863. Levanda was a maskil, an advocate of Jewish modernization and integration. He also promoted the use of the Russian language among Eastern Europe’s Jews.

Read Full

Russian journalism in the 1860s called for radical change. Alexander II had become tsar and many people believed he would bring about a total transformation of the country. In 1861, he liberated 70 million serfs. Eagerly awaiting a Jewish liberation, educated Jews wanted to help speed the process. A small group that included Levanda, along with Abraham Kovner, and Reuven Kulisher, imitated the radical Russian writers in such newspapers as Otechestvennye Zapiski (Notes of the Fatherland). In Rassvet Levanda agitated against Jewish tradition and the old ways of doing things, all of which he labeled as “ignorance” and “backwardness.” In his article in Rassvet’s first issue, “Several Words on the Jews of Russia’s Western Province,”published on May 27, 1860, Levanda presented the sharpest criticism of Jewish life in print up to that time. Visiting Igumen, a small town like any other in Belarus, Levanda found nothing to praise; everything the Jews did was bad, their way of life displayed disease, immorality, and rot. His overall appraisal: “Oh my God, what poverty! What material and moral degradation!”1

Not surprisingly, the people of the Belarussian region were infuriated by Levanda and stated in a letter to the editor that they were cancelling their subscriptions.2 The feuilleton “Awakening” expresses Levanda’s response to them and to Rabinovitch, especially to his observations about the first year of Jewish journalism in Russia. The piece begins with a confession about the vocation of a journalist: “So if anyone was to ask me now ‘what is the easiest thing in the world and what is the hardest thing?’ instead of giving the classic answer I would answer as follows: ‘The easiest thing – by which I mean the lightest thing – is …down feathers (!) …and the hardest thing is to be an employee or a staff writer in any Jewish current affairs journal.’” Although he tried to make light of the first year of Rassvet, work on the paper proved to be a school of hard knocks for him. In “Awakening” Levanda discusses whether the writer should praise Jewish communal institutions, the Jewish way of life, or whether he/she should expose flaws with the aim of improvement. He notes that the journalist who aims to help brings immense anger upon his head. He sees newspapers and especially feuilletons as one of the ways to provoke change in society. The public, he notes, needs to change if only as a first step for new Jewish institutions to develop.

Despite everything, Levanda believed the Jewish people in Russia had awakened, but rather than awakening signaling the last step of transformation, it signified the first stage, perhaps the hardest stage: “Yes, we have awakened. We were asleep for a long time, and we slept soundly, because the sky outside was gloomy, the kind of weather that just makes you want to go to bed. But may God preserve even our worst enemy from the nightmares which afflicted us – the very thought of them is enough to make your hair stand on end and goose pimples quiver across your skin. It used to be that someone would wake up suddenly, rub his eyes and fling himself out of his uncomfortable bed and walk over to the doors and windows, just to breathe in some fresh air and lighten the feeling in his chest; but – alas! – he would find those doors and windows nailed firmly shut – there was no way out; nothing else to do but gasp for air along with everybody else in that dark, cramped, stuffy and smoke-filled little hut.” In other words, the way forward toward progress is hard and the others will not make your way easier because they too would prefer to rest rather than to get up and struggle. What would Russia’s Jews choose? Levanda would risk his career on a belief in the struggle, that Russian Jews would do what was necessary for equal rights and that sacrifice would be accepted by Russia. The pogroms of 1881-82 would prove him wrong; at least that is how he felt about the violence of the Summer Storms.