Explore Feuilletons

The Letters of Uncle Yakov - Letter Two

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Buki Ben Yogli, “The Letters of Uncle Yakov – Letter Two,” 1882. Translated by Conor Daly

Since you published my first letter from Golodaevka a great deal has changed in the life of the people who live here – and, it goes without saying, the changes have not been for the better. The reason I have not written to you all this time was that I feared things here might get even worse for us if I did. Ever since the English and Americans started to take an interest in the anti-Jewish practices here I have never ceased to feel a certain trepidation that our situation might get even worse. Exactly in what way ‘worse’ – and whether they could even really get any worse than they already are – to be frank, I’m not at all sure, and that’s why I find myself in this state of trepidation…

Read Full

But it looks like fear and trepidation are feelings which we need to get used to. Before we were afraid of a pogrom happening and our fear and misery even made us cry out to the heavens: “Ah, when will they finally start beating us!” At least the beatings have happened now, thank God. You would think, wouldn’t you – now that we have been beaten and thrashed to their hearts’ content, and no less savagely than everyone else – that our feelings of trepidation should have left us, but all of a sudden along come the English …

- You know what, Rabbi Moishele, I would say to my friend, What we should do is this: we should get an article about our pogrom published in a newspaper. That might encourage good people to help us in some way or other. - Don’t even think about it, Uncle Yakov. That would only make things worse. - Why worse? - Because, as Solomon the Wise once said, “blessed is he who lives in a continual state of fear and trepidation.” The English are cunning. I’m afraid they will just use your article as a pretext to hold meetings on the subject and we will end up ashamed to look our local policeman in the eye.

You need to bear in mind that our local policeman here in Golodaevka is a very delicate person (that’s why he has ended up as a local policeman). And so he is highly sensitive to European public opinion. At the time of the Congress of Berlin he had held a fairly prominent clerical position in one of the police precincts in Berdichev, and it was thanks in part to his ceaseless efforts that the famous protest by the residents of Berdichev against [Benjamin Disraeli, the first Earl of] Beaconsfield was collated and published. In that document, as you will probably still recall, the residents of Berdichev renounced all solidarity with Beaconsfield and his underhand politics. Whether or not this protest had any role in bringing about the fall of that English prime minister, who was so hated by our local policeman, I cannot say; but we can assume that the protest did have some effect. I base this on the fact that when we received the news of the English “excesses” our local policeman was planning to lodge a counter-protest on behalf of the people of Golodaevka too against the protest of Darwin, Tyndall, and all their allies on the far side of the Atlantic ocean. Naturally we would never have dared to try and stop our local policeman, who kept going on about how the Jewish nation and Jewish stuffed fish were driving him mad and how nothing under the sun annoyed him more than the thought that we might suspect him of being hostile to us. But unfortunately along came that pogrom of ours which threw the whole initiative off track. Witnessing the pogrom had such a profound effect on his thought processes that when we went to him looking for help he was quite taken aback and just shouted to us in response: “I don’t give a fig for that Europe of yours – period!”

Now of course we are in no mood for protests. In the interests of fairness, however, I must say that most of the attacks were on our possessions and they only killed those of us who were rash enough to try and defend themselves. Nor were there any reports of rape; that is to say, our local policeman did not fill out a single case report which mentioned such matters. You will be aware that according to our laws prosecution for rape can only occur if the injured party lodges a complaint; so even if something like that did occur during that general brouhaha, the injured woman would sooner vanish through a hole in the ground than take a legal case against that rabble which, as you will also be aware, our laws still do not recognize as a legal entity. So you can draw your own conclusions from that as to how truly credible those English claims of “exaggeration” really are. I even consider it my sacred duty to warn you – if some inhabitant of Golodaevka were to tell you unexpectedly about an incident like that – for God’s sake don’t print the story… No, just assume it’s one of those “exaggerations” which is altogether more respectable to draw a discreet veil over. Because you never know, those crafty English people may run with that fact and before you know it some poor Surka or other will find herself the subject of a public meeting. After which the poor young woman will never be able to get married – if she hasn’t already managed to drown herself and her shame in the blue waters of the nearest pond…

I am not going to describe our pogrom to you. You can visualize it perfectly well without any description from me. À la guerre comme à la guerre, everything has its own rightful place. If there was anything original about our pogrom maybe it was that deep sense of disappointment which that greedy rabble must have felt when they broke into our unforgivably wretched little hovels. I can just imagine them cursing the poverty of our circumstances, which did such a poor job of burnishing our reputation as exploiters. My friend the Rabbi Moishele told me that as he sat in the corner and watched the mob at work he nearly burned with shame when those fine fellows, having ransacked his whole hovel, could find there nothing of value except a pile of useless books which even the most stupid bar-owner wouldn’t give a single glass of vodka for.

Still, we may have been poor before the pogrom, but after it we have gotten even poorer. Before we used to think that no-one could possibly be poorer than us inhabitants of Golodaevka. Oh, help us, good people! Please help us! Help us in any way you can – Russian rubles, German marks or French francs – as long as it isn’t English pounds sterling. Naturally we would be grateful for any contribution to the needy, but given the conditions which the English attach to their contributions we would feel it awkward to accept any of them – at least that is what our local policeman thinks. And we would rather die of hunger along with our wives and children than cause our policeman any unnecessary upset. After all, he has shown such concern for us lately! Oh yes, he is so concerned on our behalf! Surely someone needs to show some gratitude! His contemporaries give him no credit – only God knows if the next generation will…!

We could probably have dealt with the poverty somehow, but the worst consequence of the pogrom I think is the terrible idle void in which we find ourselves after these latest events. Our everyday affairs have completely and utterly ground to a halt. And because we have nothing to do we naturally indulge in that old habit of pouring out our emotions. That wouldn’t be such a bad thing if it were not for the fact that our emotional outpourings of late have taken on a somewhat corrosive and quarrelsome flavor – even, I would say, a touch of frenzy. Initially this had been an internalized quarrel, with each of us indulging in it alone and in private, but once we realized how sterile an activity this was we moved on to quarrelling with each other. Quarrelling with one’s neighbor is so much handier, so much juicier. And most important of all, once it is no longer a purely subjective affair, this bickering somehow becomes a matter of social import, accessible to almost everyone. But to stop the bickering from becoming merely aimless and chaotic we have split up into different factions so that we can work together and bicker and insult each other to our hearts’ content.

Oh, Lord! As if we hadn’t enough misery to deal with without all this mutual mud-slinging!

Of course the problem isn’t that we have parties, it is that each party considers itself the only one which can deliver salvation. You, for example, want to leave for America because people aren’t being beaten there – off you go to America then and Godspeed! Someone else wants to go to Turkey or to Palestine, where people aren’t being beaten either – so bon voyage! What we really need now is solidarity … to retreat in formation. Yet this is what we have come up with! When we were being beaten in Golodaevka we didn’t think of joining forces and pooling our resources to fight our troubles or to put all of our bodies jointly on the line in defense of our wives and children – no, instead we wandered off in different directions, one man to his attic, another to hide under his stove. The same thing apparently happened in Balta so that is precisely why we need to act together on this! And if we are going to act together then we will definitely need emigration committees which could direct our movement so as to save the most people possible in the most coherent way possible – otherwise, unfortunately, the scattered flock will wander off again, each in his or her own direction. For optimal efficiency we should really put our local policeman in charge of the local committee so that he can use his long horse-whip to send everyone where they need to go. But that is the very thing I fear. Because suppose that instead of Palestine he decides to chase us off to Mongolia or somewhere like that?

Sinful me, I confess that I had never even considered emigrating. It’s not that it didn’t hurt me to be beaten, but because, first of all, we have no physical means of going anywhere: there is no manna falling from heaven onto the railway tracks; the road from Egypt to the promised land is now paved by a whole civilization with its foibles and consumption habits. And secondly … now how should I put this… I mean, it would be a real pity to have to say farewell to my land of birth, to my “Russian homeland”… Now for God’s sake don’t laugh at me; it’s bad enough to be laughed at by others. You must believe me when I say that I am unable to pronounce that phrase without my whole facial expression changing and without the blood rushing into my head. It’s a bitter feeling and I am ashamed to admit it.

Just think. Ten years ago my own nephews were continually upbraiding me for not being able to read or write in Russian properly even though I was a Russian citizen; they used to criticize me for my Old Testament mentality, my detachment, my alienation etc. And I used to admit that they were right. But now, in my advancing years, out here in the middle of nowhere, a long way from all that is Russian, I and my faithful friend Rabbi Moishele the German have taken with a passion to our Russian ABC and naturally we have not stopped there. And, my God, how much effort, how many sleepless nights did it take for us to master that foreign language, that foreign literature. And now when, finding yourself far away from everything that is Russian, you start feeling that you actually are Russian, when in your conversations and thoughts you rejoice at Russian joys and feel sad at Russian sorrows, when in your conversations and your thoughts you start to take pride in “our” Russian poets, “our” Russian scholars, even “our Russian” Antokolsky, “our Russian” Rubenstein – when suddenly, bang! first one pogrom, then another, and a third one… and you are dumbstruck, and in that dumbstruck state you look around you and ask in a frightened voice: where has all that “our Russian” stuff gone? And when that once dear expression (indeed maybe it is an expression which is still dear to you) trips off your tongue without you realizing it, you feel kind of guilty, you bite your lip and think: lucky our local policeman didn’t hear me say that; he would have split himself laughing!

Well may you laugh, ladies and gentlemen! But me, I get a rush of blood to the head when I even think about it…

Just the other day my elder nephew came back from university for his holidays. He found me absorbed, deep in a book by one of my favorite Russian poets.

- What are you doing there, uncle Yakov? he asked me, right after his initial words of greeting, and he bent over my book. - As you see, I am reading one of our Russ… I started to answer, but broke off sheepishly. - Oh, uncle, uncle I can see you are a hopeless case! What do you mean “our Russian”? What is Russia to you and what are you to Russia? High time now to finally drop all those pipe-dreams and actually do something real.

And with these words he flung the book I had been reading onto the floor, then took another small book out of his pocket and turned back the title page for me.

It was Teach Yourself English – The Modern Method.

- We’re going to America, Uncle, so we need to know the language of our future homeland, – that was how my nephew justified his ignorant action – Study it yourself, Uncle!

More study to be done then! Lord, how is it that other people can have a homeland without having to know anything in particular whereas we are always chasing this elusive something, always studying away, studying for nothing. I have spent more than half my life studying the languages of my former homelands on the banks of the Jordan and the Euphrates, then my twilight years studying the language of my true homeland and now, when I am almost on my deathbed, I am told to go and study the language of some mysterious future homeland! But what if it turns out that my diligence never receives the recognition it deserves and in a few years’ time I have to go looking for a new ‘teach yourself’ manual of some other language, spoken in some other future homeland? It’s awful to think of myself arriving one day like some crazed linguist into that celestial homeland where all languages will have fallen equally silent…

I had no choice: I pulled myself together and started into the ‘teach yourself’ book and in my mind I was already starting to use that unfamiliar English tongue to deliver speeches in the Jewish parliament of a future Jewish state in North America, when suddenly along arrived my younger nephew.

- What are you working on there, Uncle? - English grammar, as you see – after all, we are going to America. - America! No way. Everyone who goes to America is lost to Jewry. Surely you won’t want to increase by one the number of the lost? No, dear Uncle, either we die here or we go Palestine! The banner has been raised! He who is not with us is against us!

To be honest I have always cherished in my soul a certain weakness for the now desolate but once flourishing land of Palestine. I have always kept the idea of a return to Palestine – the idea that was entrusted to us by the prophets – concealed in the depths of my heart, like a sacred aspiration. I used to embrace that idea in my heart back in those days when merely mentioning it out loud conjured up wry smiles on the lips of my friends and roars of laughter from that same nephew who was now backing it to the hilt. I would even say that I had always thought that this idea, which had been the dominant motif in most Jewish prayers, is consciously or unconsciously present in every Jewish soul; that this idea, which has permeated our history like a bright line, connecting the present with the past on the one hand and with the future on the other – that this idea alone preserved the Jewish people amidst all the sufferings and persecutions which have afflicted it. Nevertheless I must admit that I found the shrill and triumphant tone of my nephew somewhat disconcerting. I had always thought that we had not yet suffered enough for this idea to come to pass … and that before Palestine could be colonized we still needed, in the words of Nachum Ish Gamzu, to “learn a great deal and absorb the lessons we have learned.” But if events are now forcing us there, then, so that idea may triumph, it is essential that the people who go there are not those who are “called” but the those who are “chosen”; not those who have nothing to lose, but those who are already in the full possession of their material and spiritual strength yet desire to gain still more. May all people go there who hold their God in their hearts, who are capable of working and toiling not just for their own personal benefit but in the name of the idea which inspires them; but I pray that these pioneers – when they think of all those other people who remain true to their homeland, whether it be a homeland of long standing or one just newly acquired – will not consider them as ‘lost’ to Jewry and its ideals. I never considered as ‘lost’ to Jewry all those millions of Jews who ended up scattered around Babylon and other countries during the time of Ezra and Nehemiah after only a small group of pioneers had emigrated to Palestine as agreed by Cyrus. Both groups discharged their debt to history. Were they not the same scattered millions who carried the Jewish people on their shoulders when the whole population of Judea at the time had been destroyed and sold into slavery by the Roman barbarians?

The whole strength of Jewry does not depend on physical togetherness alone! A scattered and dispersed Jewry has outlived more than one nation which had been close-knit and rooted to its land. Our Talmudic scholars knew that well; they used to say: “The Lord has granted a blessing to Israel by scattering it amongst the nations.” As a close-knit people rooted to the land, as a people in the strategic meaning of that word, the Jews were crushed under the pressure of the Roman colossus, but as a nationality, as the incarnation of an eternal historical idea, they triumphed over that colossus. Nationality relates to a people in the same way as animal life relates to plant life. If you tear a plant out of the soil which nourishes it, it will wither and die; whereas nationality, like an animal organism, lives by virtue of its own inner strength, its historical mission. And the strength of Jewry lies in its national inheritance, in the belief bequeathed to it by the prophets that a day will come when the wolf will live peacefully alongside the lamb, when people “shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks; when nation shall not lift up sword against nation, and neither shall they train for war anymore.” And if Jewry is fated ever to rise again as a “people,” and if as a people it ever fulfils the mission that it has set for itself, then its scattered sons – thanks to that revulsion towards blood and the sword which has become so deeply rooted in them – will infect others with that revulsion and so will work on in that way for the benefit of all humanity.

My nephew had been listening to me attentively at first, but after a while he was clearly seized by a strong feeling of impatience, because he almost seemed to stop listening. In the end he could bear it no more and burst out:

- Enough of your philosophizing, Uncle. It’s time we went “home” now, all of us. Get yourself ready for the journey because we are going to Palestine.

And with these words he flung the ‘teach yourself English’ book, still open in front of me, onto the floor, then opened up another modest little volume, dotted all over with some kind of tiny squiggles, which made my eyes ripple, prodded it with his finger and added:

- While we are waiting, Uncle, study this. It is the language of our future homeland.

“A New Guide to Arabic Grammar” is what I read on the book’s title page, and I started to study it, sighing periodically and repeating silently in my thoughts that highly significant phrase: “Time to go home now!”

- What do you think, Rabbi Moishsele, I asked my friend. Is it time for us to go home or isn’t it? - Do you mean so that you can change the name of Palestine back to Judea? - Well, that would be one reason to go, yes. - I think the time to go home has long since arrived. For my part, I am ready to leave right now. - Can you already speak Arabic then? - No, Uncle Yakov. That’s something I will get around to; but look, I am ready in this respect. It says in the Talmud that the son of David will not come until the last penny disappears from your pocket. You know that it's been a long time since I had even a penny to my name. We’re only still here because there are still a few gvirim left who have survived so far, but wait for another two or three pogroms and we’ll all be ready… As long as it’s not too late by then – added Rabbi Moishele, and I could hear the irritation in his voice as he ended the conversation.

You should know that Rabbi Moishele has become pretty much unrecognizable of late: you could say that he has gone to seed and become quite depressed. He doesn’t even like to indulge in emotional outpourings any more. The mutual squabbling which has become so fashionable of late has left him totally dispirited. On the one hand we have those elated exclamations, made on an empty stomach, like: “The banner has been raised,” “Time to go back home!” when actually what we are being asked for is not a banner but some daily bread; and on the other hand the malicious taunts of our gvirim, who reject the banner but deny their neighbor bread... On the one hand we have those naïve “diplomats of the future” who hold their cards out on public display, who sit here in Golodaevka but in own their minds are fighting for Palestine, oblivious of the fact that although virtue may be worthy it is not always useful; and on the other hand those subtle “diplomats of the present,” who are so skilled at exploiting love of homeland as a cover so as to conceal a sublime indifference towards their fellow man…

Do you remember how in my first letter how I told you that wonderful idea my friend had about setting up a company that would provide insurance against pogroms, whereby each Jew would be obliged to contribute a certain percentage of his income so as to save him from death from starvation if a pogrom were to come along? You called my letter a “feuilleton” and of course, as everybody knows, serious people do not take feuilletons seriously. So the idea never went anywhere. Rabbi Moishele did try to set up a sort of local society, but once again it didn’t work out for him. Citing fears that someone might use the insurance premium to emigrate with, our gvirim refused to make their contributions; and as for the dividend generated on income received from our ordinary residents, well, and let’s keep this just between us, you’re not going to travel very far on it. But now we’ve just had a pogrom and most of what used to be our gvirim have lost their shirts and it is they who are dying of hunger. Wouldn’t those funds have come in handy now!

After all, it is possible that if we had an insurance society like that, with a solid capital base of course, then pogroms might not even occur… So as it turns out we have lost everything only because of a fear that someone might leave our beloved homeland. In other words, our love for our homeland – that is, our total indifference to the sufferings of our fellow human beings – is to blame for everything. As if we were to say: go ahead then, terrorize us, burn us, rape us, do whatever you want with us because not only will we not leave ourselves, but we won’t give anyone else as much as a bean to leave with either. And they still say we aren’t patriots!

I need to tell you one more thing though, and that is that as a result of all this my friend decided not to establish an insurance society, or any other society for that matter, which made him the target of pitiless attacks from all kinds of banner-bearers from both the American and the Palestinian camps. For a while he was even being accused of colluding with our gvirim, an accusation which particularly annoyed him. It took me a long time to get any explanation out of him as to why his thinking had changed. To all my various questions he would usually answer me with this well-known Talmudic proverb: “Woe is me if I speak, and woe is me if I say nothing;” and then would wave his hand dismissively and start talking about something completely different. It was only the other day that everything became crystal clear to me.

It so happened that one day our Golodaevka scribe Rabbi Mendele the Lawman called by and found us both stuck into that Arabic grammar, which we had started studying upon the insistence of my younger nephew. Now, Rabbi Mendele the Lawman is a walking newspaper, who is always able to give you the most up-to-date political news, whether international or domestic, and will himself swear as to the veracity of this news, because he maintains important contacts with the world of officialdom in the person of our local policeman with whom he happens to be on intimate terms. It is even said that the local policeman deigned to visit him at home (before the pogrom of course) and sample the stuffed fish à la juif prepared so skillfully by the fiancée of Rabbi Mendele the Lawman. But that is beside the point.

- What are you working on there? he asked me, with a side-glance at our scribblings.

I explained.

- So you are going to Palestine then? - No, this is just in case.

He looked at me in a serious way, then straightened up and asked:

- Do you love your homeland? - Yes, I do. - So you will stay in Russia then? - I will for as long as they don’t throw me out. - In that case I have some good news for you: put away your scribblings and get stuck into some real work – there is no time to lose.

And flinging aside the Arabic grammar, he opened up a brand new book the title page of which read: “A new guide to Central Asia – appendix includes conversations in the Kalmyk, Teke, Mongolian and Tibetan dialects.”

- Why the hell would I need all those dialects? - They are the languages of our new homelands. Get yourselves ready for the journey. We are going to Mongolia.

My eyes widened in fear.

- But what will we do there? - We won’t do anything there. People say it is a beautiful country where only figs and grapes grow. So we will just sit there without a care in the world, “everyone will sit under their own vine and under their own fig tree, ”1 without any fear of pogroms (since there are no ‘indigenous’ people there yet) and our only obligation will be to develop trade and industry there in the same way as we did before in southern Russia. And if we manage to fulfil this obligation properly so that even the indigenous people will be able to move there, they will then transfer us to some other part of Mongolia where even more fig trees and vine groves grow and where once more we will have to develop trade and commerce, and so on ad infinitum. - But those places are terribly far away! How are we supposed to get there? - Just set up your own pogrom insurance society and stipulate that the pogrom compensation payment will only be made to people who go to Mongolia.

Rabbi Moishele had not taken any part in the conversation up to this point but now he could bear it no more and making a despairing hand gesture spoke as follows:

- No, Rabbi Mendele, that won’t be happening: we won’t be going to any Mongolia. - But fig trees grow there, they say… - Yes I know, I know the kind of fig trees that grow there; but even if there were little golden apples growing there, I still won’t be going. - But I’m sure you love Russia… - I love Russia no less than you do, but I won’t be going to Mongolia. - Explain then why not. - Here’s why not. There is a story in the Talmud about how the Romans forbade the Jews from engaging in science under pain of death. For the Jews this was a harsh and impossible law and they needed to “get around it.” The famous teacher Rabbi Akiva was one of those who got around it, and he had a following of 24,000 pupils. He was once asked by a certain Pappos ben Yehuda: “Is it worth putting your life in danger for the sake of science? If the Romans find out about it, that will be the end of you.” And this is how Rabbi Akiva answered him: Let me tell you a parable. There was once a fox who was walking along a river bank when he saw fish rushing from one side to the other in fear, as if seeking refuge from an imminent danger. – “What are you rushing about for, dear fish?” the fox asked them. “We are running away from the terrible nets that evil people are casting all round about in order to kill us.” “Why,” said the fox, “would you want to live in water, this treacherous element, where you are subject to constant danger; wouldn’t you be better off coming up here onto dry land and live with me, in a secluded grove, in peace and contentment, just as my ancestors used to live together alongside yours?..” To which the fish answered: “Fox, aren’t you the creature who is rumored to be the most cunning of all the animals? If we have to worry for our life all the time as it is here in what is our natural element, you can be sure that outside that element we would not last a single minute: there we would soon die even without any malice from people.” - Do you see now? If here, in what is pretty much the center of civilization, in full sight of the whole of enlightened Europe, we are robbed, killed and dishonored in broad daylight, and have nobody to defend us, what can we expect from the wild inhabitants of a wild and desolate Mongolia? There we will die even without any malice from people. Civilization is our natural element: if civilization has not saved us from evil people, it is not civilization itself that is responsible for our sufferings, but the incomplete nature of that civilization, indeed its absence. For it is on civilization alone that we must continue to rely – which we must work to develop, here and everywhere. And if here, in my homeland, my life is ever made so “inconvenient” that it finally becomes “intolerable,” then I will go to Palestine, to America – wherever indeed the breath of civilization reaches. The column of smoke belching from a railway locomotive – that faithful companion of modern civilization – will be my “column of fire” along the route of my wanderings; I will even go to Mesopotamia if that happens to be the direction in which that fiery column points me, but to Mongolia I will not go – no, not for anything! - You know, Uncle Yakov, Rabbi Moishele added, turning to me abruptly. – You need to write that letter to the newspapers right now. - You don’t think things will be worse if I do? - No, they couldn’t get any worse; write and tell them that we won’t be going to Mongolia. Absolutely no way will we go there. Write it just like that!

So that is what I have written. Uncle Yakov

Certified as true and correct. Buki ben Yogli

- Micah 4:4. ↩

Commentary

Buki Ben Yogli, “The Letters of Uncle Yakov – Letter Two,” 1882. Commentary by Brian Horowitz

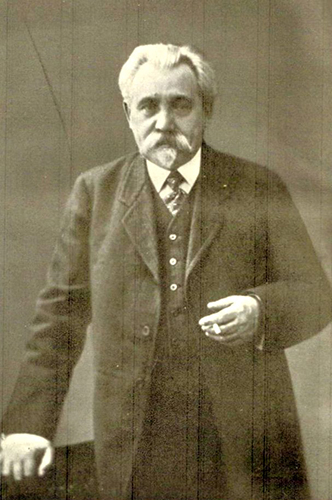

This feuilleton, “Letter from Uncle Jacob” ostensibly focuses on the confusion of educated Jews during the pogrom years in Russia of 1881-82. Buki Ben Yogli, the pseudonym of the Russian-Jewish author Leib Katzenel’son (1846-1917), was uniquely placed to deal with these issues. Right away he asks the accursed question for Jews: “what to do” in response to rape, beatings, and even killing during the first pogroms of 1881-82. After the initial shock, Jews began to wonder, what next? Uncle Jacob, a stand-in voice of the author himself used in two feuilletons from this time, lists the various alternatives. We see him learning English in preparation for emigration to the United States. After his enthusiasm for the United States wanes, we encounter him studying Arabic for eventual emigration to Palestine. That too has downsides. Then he is learning Mongolian in the hope of moving to Russia's Far East. Nothing appears as attractive as remaining in Western Russia with its familiar terrain, culture, people, and Jewish way of life.

Read Full

Katzenel’son’s position makes sense in light of who he was. His father died when he was very young and he grew up in Bobruisk in Belarus (then Belorussia). He was poor and often lived as an itinerant, moving from place to place. He became extremely adept at Talmud and was considered a genius (ilui). In 1866, he enrolled in the government’s Rabbinical Seminary in Zhitomir. When he finished in 1872, he started medical school and finished just in time to serve in the Russian-Turkish war. After the war, he moved to St. Petersburg and found a position at the Alexandrov Hospital and began writing for the Hebrew and Russian press. The feuilleton that appears here first appeared in the weekly newspaper, Russkii Evrei (Russian Jew) in 1882. The essays published in Russkii Evrei were republished as a collection in 1902 (Buki-Ben-Yogli, Mysli i grezy (Thoughts and Inklings), St. Petersburg: Yosif Lur’e, 1902).

Katzenel’son belonged to the Petersburg elite, a small group of hyper-talented and educated individuals who gained the right to live in the capital city by virtue of their education (in case of this writer) or wealth (First Guild status). He is interesting as a feuilleton writer because of his proud, almost nationalist, stance. In contrast to Leo Pinsker, who criticized the non-Jewish world, saying that anti-Semitism was an incurable disease in his book, Autoemancipation (1882), Buki Ben Yogli looked inward. He saw much that was good in Russia and realized the problems that existed in other places: competition and xenophobia in the United States; Turkish interference and Arab hostility in Eretz Israel; and who knows what might be awaiting immigrants in Mongolia. Things didn’t look good right now in Russia, but who could tell which of the alternatives might be better in the future?

Katzenel’son himself chose to stay in Russia. He devoted his work as a journalist, historian, and doctor to the improvement of the lives of Russians and Russia’s Jews. Interestingly, early on he supported the renaissance of the Hebrew language, but did not expect that Zionism would prove effective. However, he visited Eretz Israel in 1909, and was warmly received throughout the country as a Hebraist who played an important role in promoting Hebrew, including writing feuilletons in Hebrew newspapers.

This feuilleton argues, using the words of a wise and older Uncle Jacob, that there are problems for Jews everywhere. Russia is no exception, but it has one advantage: it is home and home means a preponderance of Jews with the same problems. When tragedy breaks out (such as in 1881-82), it is a real consolation to be among one’s people.