Explore Feuilletons

The Disappeared Sukkah

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

URI

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Abraham Philip Samson, “The Disappeared Sukkah,” 19451. Translated by Eli Rosenblatt

In one of the insignificant districts of the city, in a shabby little building whose walls on the street side are already telling you that there is no luxury within, and likely also no luck, the old Jewish woman lives with her grandson, who earns a living through manual labor and the occasional trade.2 For many years she has been supported by the Ashkenazic Congregation and with the little that her grandson brings home and the gifts now and then from friends, she quietly spends the last days of her life. Although she cannot be counted among the strictly observant Israelites of the congregation, she has loved the prayer service since her earliest childhood and can safely be counted among the synagogue-goers. Since the death of her husband and later the loss of her only son, she was effectively reduced to beggary. She was forced to call on the support of the Jewish Poor Board, and now she can no longer visit the Synagogue because of old age and illness. When the High Holidays approach and the additional distribution of charity funds has taken place, she can afford the luxury of buying a few extra items. Thus, with her half-blind eyes, she recently managed to make a new cape for Yom Kippur for Bram, her grandson, and she imagines that she can have the frayed Hebrew letters on his prayer shawl renewed by Passover. When the High Holidays approach, she reminds Bram to ensure that he will arrive in the Synagogue on time. She will also make sure that the boy does not disappoint her by coming home from the Feast of Tabernacles without bringing her a piece of “Amoetsie.” The boy knows that she has acquaintances who profess a different religion, but who appreciate having such a piece of bread.3

But this year Bram would disappoint her, because on the morning of the New Year's holiday he sprained his leg and, with a swollen ankle, he was now at home and unable to experience the Synagogue services during the holidays. Therefore, he did not know that on Rosh Hashanah the Secretary announced that there would be no Sukkah this year, and that this service will be held at the sister congregation of the Portuguese Israelites.4

And since none of the absentees could know what the Secretary had read, expecting that it was merely the usual announcements, they knew that as always, no bread would be distributed outside the booth, but they did not know that there would be no booth in the yard of the Ashkenazic synagogue. Should grandmother miss her bread this year, now that Bram is unable to attend the service? A solution has to be found! Cornelis, who lives on the property, has a Sunday suit that suits him well. What if he went to shul? Everyone is welcome. Grandmother will therefore ask Cornelis to attend the service. The evening service does not last long and the bread is fresh and crunchy and the pieces are quite large. If Cornelis is not too modest, he can have enough provisions for himself, grandmother, and Bram. Cornelis had one objection, however.

His hat was not fit for the purpose and he didn't want to be laughed at. Fortunately, Bram had bought a new castor hat with a view to the coming days, and it would fit Cornelis well. And so it happened that on the evening of Sukkot, Cornelis was all dressed up and walked the long way to the Synagogue on Keizerstraat. But who could describe his astonishment when he saw nowhere in the yard a sukkah? How could that be? He walked through the back of the yard and searched. Perhaps this year they chose another place to put it, but nowhere could a trace be discovered. He doesn't even dare to ask the shammash, people would look at him strangely and perhaps find him cheeky too. He saw no acquaintance in the yard. Suddenly he realized that the Synagogue was not open… So something strange must have happened. The booth has been stolen, collapsed, or burned, and everything has already been cleared away. He then returned home as fast as his legs could carry him, and Grandmother and Bram looked up in amazement when he entered. “Young man! How is it possible that you are home so early? And where is my bread?” asked the old woman in the same breath. “The Cabana is gone, robbed or burned, I ... I don't know.”5 “You're a liar or a very stupid youth,” she shouted. “You don't even know where our Synagogue is.” Bram is calmer than Grandmother and says: “Maybe there is no service in our synagogue this year, because no one is available.” “Then you must go back, youth, to the Portuguese synagogue!” “I go such a long way again? I don't think so! Here you have your hat back, Bram, and I'm going to fold my suit neatly for Sunday afternoon.” And so Cornelis left the two people alone, desiring amoetsie, and went into the yard. During the silence that followed, Grandmother sat in a pensive pose. A series of events went through her mind like a movie. Her youth, the full synagogue, the people sitting like herrings in a barrel on the hard benches of the Cabana! How times have changed. How did people let it get to this point?

Is it only the death and departure from Suriname that have caused these things?

Is it just for this year? Will the new year bring a revival, or will the misery we Jews have experienced in Europe during the last few years leave its mark on Jewish life here? Not a piece of blessed bread this year! How is it possible! She was interrupted in her meditation by a knock on the door. Jacob, Bram's “Portuguese” friend, stepped inside6. Something protruded from his pocket and before Bram could say anything, Jacob brought out a piece of bread that he gave to grandma, “I knew you were sick and could not attend the service, so I took care of you and the old woman,” he said triumphantly. “May God bless you, my youth, that you have thought of us, and now look at the table in the hallway. There you will find a nice bacove, you can have it.”7 As Jacob hurried to get what was offered, he heard softly Hamoetsie lechem mienha-arets.8

A ph samson

- A Sukkah is a temporary dwelling erected by Jews during the holiday of Sukkot, which commemorates the dwelling of the Israelites in the Egyptian wilderness. ↩

- Thank you to Gidon van Emden for his comments on the translation. ↩

- Amoetsie is the Creole term, derived from Western Sephardic Hebrew, for Challah bread, used during Paramaribo’s Jewish sabbath and holiday meal. Baked in large quantities on Sukkot and distributed by the Jewish community to the city’s poor, this braided loaf was valued by the Afro-Creole population for its uses in Christian and Winti rituals. ↩

- Portuguese Israelites is the standard term for the Western Sephardic Jews that established the first Jewish communities in the Americas. By the early 18th century, Suriname’s Ashkenazic Jews established their own synagogue, thereby creating two separately incorporated Jewish communities, a common practice in European metropoles as well. ↩

- Cabana is a commonly used Sranan Tongo (Surinamese Creole) term for the Sukkah, used frequently by local Jews and non-Jews to refer to the Sukkah. The journal Teroenga, in which this feuilleton appears, frequently refers to the Sukkah as a Cabana in order to accentuate the local custom to decorate with local flowers and ornamentation. ↩

- Portuguese Jews, the first Jewish settlers in Suriname, maintained their own synagogue and communal organizations apart from the larger Ashkenazic congregation. ↩

- A Surinamese banana. ↩

- The Hebrew blessing over the bread. ↩

Commentary

Abraham Philip Samson, “The Disappeared Sukkah,” 1945. Commentary by Eli Rosenblatt

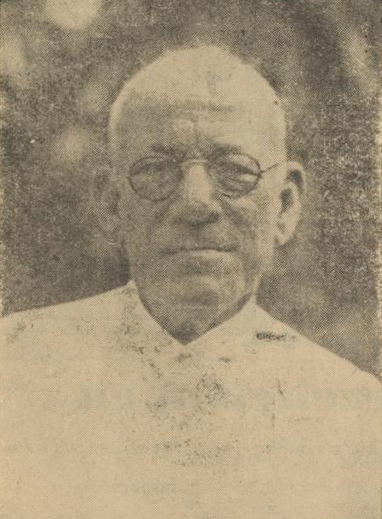

Suriname, which gained independence from the Netherlands in 1975, is a culturally Caribbean country located on the northeastern coast of South America. The author, Abraham Philip Samson (1872-1959), was a pharmacist, teacher, and a pillar of the Ashkenazic synagogue community, established in the early 1700s, in the capital city of Paramaribo. This feuilleton is one of his contributions to the monthly journal of the Surinamese Jewish intelligentsia, Teroenga. Samson’s writings ranged from biblical exegesis to poetry in a mixture of Dutch and Sranan Tongo, the creole language spoken by all Surinamese. Though the journal appeared on a monthly basis between 1939 and 1969, the editors did not frequently publish feuilletons or other forms of creative writing, preferring to provide readers with religious edification, historical portraits of Suriname’s Jewish past, and information about Jewish life in the United States, Palestine, Holland, and Eastern Europe in the clutches of German violence.

Read Full

Samson’s feuilleton is presented as a parable, which takes up the reasons for the depletion of Paramaribo’s synagogue life. While the synagogue’s decline had been attributed by many to emigration and the death of prominent community members, the piece focuses on the demoralization of the local Jewish community in the immediate aftermath of World War Two, a moment when the community had recently learned that over one hundred Surinamese Jews living in the Netherlands had been deported to their death, including Abraham Philip Samson’s son Marcus. In its portrayal of inter-religious contact, and the effects of poverty on the broader community of Afro-Creole Surinamese, Samson deftly presents Christian-Jewish antagonism and threat of arson by local Christians. When Cornelis arrives at the synagogue yard and finds that the Sukkah is nowhere to be found, he immediately suspects arson and theft. This evocation of violence and instability points to the fact that this piece was written in a period of labor unrest in Suriname, and the rise of Afro-Creole nationalism in a Christian key. At the same time, the history of Iberian Jewish participation in the slavocracy bound generations of Surinamese Jews to local Afro-Creole culture through genes, space, and history. The Jewish characters acknowledge that challah from the Sukkah played an important role in Winti, an Afro-Caribbean religious practice borne in Suriname from West African and Christian elements.

Questions about the Jewish future in Suriname are central to this feuilleton, and were regularly evoked and debated in the pages of Teroenga. While Suriname’s Jewish community had existed since the earliest days of settlement, the population of Jews affiliated with the Sephardic and Ashkenazic communities had steadily decreased since the abolition of slavery in 1863. This decline was caused by many factors, including but not limited to the success of Christian missionaries among families of mixed African and Jewish ancestry, the emigration of Surinamese Jews to the Netherlands and elsewhere, and the impoverishment of the Jewish community along with the rest of the colony’s population. Teroenga’s editors lamented the inability of local Jews to find European or American rabbis and teachers willing to remain in a small, poor Jewish community characterized by its harsh, tropical climate and distinct practices infused with Afro-Creole cultural elements. In this feuilleton, we encounter these themes of isolation, poverty, Christian-Jewish antagonism, and numerical decline. By the 1950s, Samson’s contributions to Teroenga reflect the journal’s increasingly Zionist sentiment and the articulation of new, Caribbean Jewish forms of anti-colonial political thought and literary expression bound to Suriname’s long history of Jewish cultural autonomy.