Explore Feuilletons

Memories of Mobilization: Yom Kippur in the Ma‘arif Mellah

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Author unknown, “Memories of Mobilization: Yom Kippur in the Ma‘arif Mellah,” 1921. Translated by Academic Language Experts team, John Peate

It was the eve of Yom Kippur and we had returned from exercises. The canteen bell sounded, but we Israelite conscripts were permitted to go to the mellah1 in Ma‘arif, a few kilometers from Casbah Ben Ahmed, where we were garrisoned.

We headed westward over successive plateaus that were traversed by a beautiful trail between tilled fields. There were few trees on the horizon but in the farthest distance was the blue outline of the Mdakra mountains. We marched at a lively pace since we had to arrive before sundown.

We climbed a final incline and there, amidst the somber green of the cactuses and the grayish green of the fig trees, we saw a mass of cabins covered in thatch and little white houses with terraces and black tents. Ma‘arif.

They had seen us from afar and a crowd of Jews ran barefoot to meet us, each with a black yarmulke on the upper forehead and a fulsome calico robe that rippled with every movement and swelled in white billows in the wind.

What expressions of delight and fervor we were met with! Each one took a soldier by the arm and proudly marched along with him, those who had arrived late were disappointed to have to return alone. The Arabs watched us in procession with a benignly childlike curiosity.

I was the guest of a local notable who owned a stone-built house at the rear of the quarter. Facing a square courtyard was a vast, immaculate room with rugs on the floor and a mattress along the wall.

He did not waste time in idle chatter. It was late and we quickly sat at table. It was already the hour for prayer, the time when the great fast of atonement would begin. The meal was copious but far too spicy. The mistress of the house reclined alongside us, encouraging us to help ourselves to the plenty on offer.

We arrived at the temple via an infinity of narrow passageways covered with a thick blanket of fumes kicked up by every animal in creation – donkeys, mules, horses, and camels – in and amongst which farmyard birds pecked away. The doors were open on the immaculate little houses, whitened with quicklime for the festival, and women and young girls who had decked themselves in their best high days clothes looked on at us with a touching pride. We were Jews and soldiers of conquering France at one and the same time. We ruled over the Arabs. It was complicated matter for the crude intelligence of country-dwelling Jewesses. There was a mystery to it that they did not seek to elucidate. They were joyful and smiled at us with familiarity.

The temple, a vast earthen chamber with little skylights built into the ceiling was already jam-packed. There were wooden benches all around the walls, in the center of it all the bimah, and mats laid on the ground in any spare spaces between them. On the back wall there was a small white wood ark for the scrolls of the Torah. Oil lamps hung from ceiling beams on chains, giving off a black smoke and a powerful odor.

A few youngsters were ejected to make room for us, and all the children were otherwise left outside anyway. They gravitated towards the door and tried to worm their way in behind larger individuals, but the cheih2 pre-empted them with punches and kicks. The poor little things remained utterly contrite, having been so keen to take part in the prayers. Their whiny little voices replied “amen” fervently to the blessings offered in the service. When it ended, they went off to fool about and brawl among the animals. I could see them capering around in the brilliant light of the moon.

The prayers went on at length, their persistent chant touching the heart. Recalling that emotion is poignant when one thinks of the tragic events that would ensue on the frontline.

To be continued.

1 in the middle of this sentence and another at the end.2

Commentary

Author unknown, “Memories of Mobilization: Yom Kippur in the Ma‘arif Mellah,” 1921. Commentary by David Guedj, translated by Academic Language Experts team, Joshua Amaru

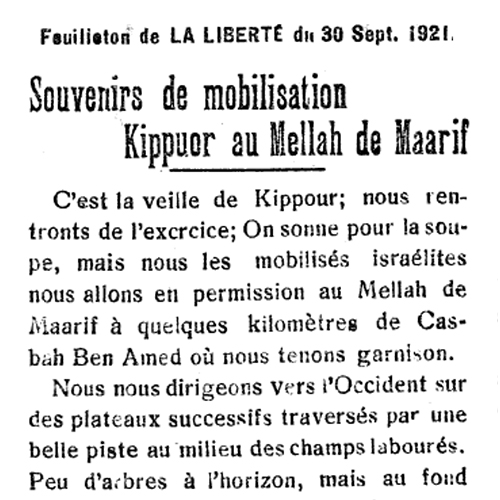

The feuilleton “Memories of Mobilization: Yom Kippur in the Ma‘arif Mellah” (Souvenirs de mobilisation Kippuor au Mellah de Haarif) was published in La Liberté, a newspaper published in Tangier, northern Morocco, from 1915 to 1922 by Solomon Benayoun. Benayoun printed the paper at the French-Hebrew Imprimerie Française du Maroc, which he owned. It appeared in two editions—La Liberté in French and El Horria in Judeo-Arabic—that were different in nature. The French edition featured journalistic articles on a broad range of topics, written by local Jewish intellectuals, occasionally accompanied by feuilletons. In the Judeo-Arabic newspaper, by constrast, few articles appeared and most of the space was devoted to reports gleaned from the world Jewish press. In its subheading, the newspaper declared itself a defender of the interests of Moroccan Jewry (journal de défense des intérêts israélites au Maroc), and featured reports from the various Jewish communities in Morocco and discussions of urgent matters that troubled them. Similarly, it published reports about the lives of Jews in Europe and Eretz Israel/Palestine as well as Zionist activity in the Jewish world.

Read Full

Feuilletons appeared in the French edition in their own section, “Feuilleton de LA LIBERTÉ.” The section appeared in the typical site for feuilletons in newspapers: on the second of the two pages of the paper, below the line. The feuilleton genre that appeared in this periodical, just like other North African newspapers published in in Judeo-Arabic, French, Spanish, or Italian, was imported from Europe, foremost from France. The French-language newspapers in North Africa carried feuilletons that were common in France, such as serialized travelogues, the “feuilleton novel” (popular novels in installments), and articles on cultural matters.

The feuilleton before us belongs to the serialized travelogue genre and was published in La Liberté in four installments. This is the first part of the travelogue, which appeared on September 30, 1921. The author’s name is absent, but one may infer from the content that he was Jewish, apparently French, and served with the French forces that were present in Morocco from 1912 to 1956, the period of French protectorate rule. In his feuilleton, this Jewish soldier describes Yom Kippur eve, when he and other Jewish soldiers received a furlough from military training to celebrate their festival. They marched off to the Jewish community nearest the military base in Ma‘arif. The soldier describes the warm reception that the community gave him and his fellow Jewish soldiers: his experience in a private home, the pre-fast meal, and the Yom Kippur evening prayers. He describes the synagogue and, as he does so, elaborates on relations between rich and poor and young and old. I presume that this series of feuilletons had appeared in a Jewish newspaper in France and that Benayoun, the editor of La Liberté, found it of interest due to its account of Yom Kippur in Morocco and therefore published it in his newspaper. Notably, the European Jewish soldier’s account is free of any Orientalist perspective; he describes the encounter with his fellow Jews with intimacy, sympathy, and appreciation.

Further Reading:

- Pierre Cohen, La presse juive marocaine éditée au Maroc, 1870–1963 (Rabat, 2007).