Explore Feuilletons

Jew or European

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Keywords

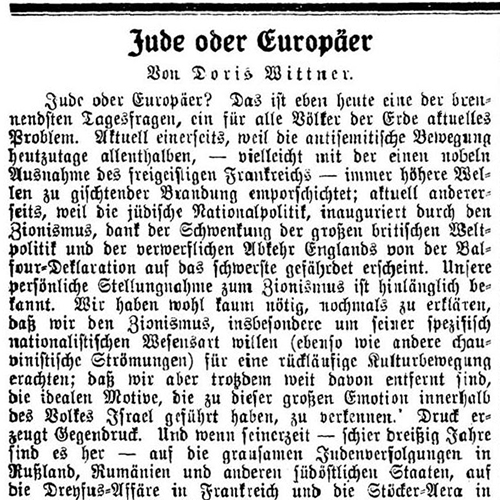

Original Text

Translation

Doris Wittner, “Jew or European,” 1930. Translated by Kerry Wallach

Jew or European? That is simply one of the most burning issues of the day, a current problem for all peoples of the Earth. Current on the one hand because the antisemitic movement is universal nowadays—maybe with the one noble exception of freethinking France—always higher waves ascending in layers in the spraying surf. Current on the other hand because Jewish national politics, inaugurated with Zionism, thanks to the pivoting of the great British world politics and the reprehensible retreat by England from the Balfour Declaration, appears to affect the most vulnerable. Our personal position toward Zionism is well known. We scarcely need to explain again that we consider Zionism, especially because of its specifically nationalistic character (like other chauvinistic movements), to be a regressive cultural movement. But despite this we are a long way from mistaking the ideals that have led to this great emotion within the people of Israel. Pressure generates counterpressure. And if in those days—a mere 30 years have passed—in response to the cruel persecution of the Jews in Russia, Romania, and other southeastern States, to the Dreyfus Affair in France, and the Stöcker era in Germany, a reaction occurred that believed it would be able to fulfill the ancient longing of Israel for the land of its fathers and the related soil, then we are the last to be in a position to contest the roots of such an ideology. Another point is the ideal for which the soulful hands of dreamers and fanatics attempt to reach in a vacuum; another is the harsh reality about which must be said: “Where space is limited, things clash against each other.”

Read Full

We have always accepted the validity of the thesis that West European Jews might be able to feel like citizens of the land to which they belonged according to birth, language, and cultural community; that they are allowed to practice their religious traditions and convictions fervently on the side without deriving any national special privileges from their community of origin [Stammesgemeinschaft]. For the East European Jew, who was guaranteed equal rights almost nowhere, other imponderables and perhaps also intuitive laws prevail.

But if today the Danish writer Henri Nathansen presents us with a portrait of Georg Brandes with the title “Jew or European” (Verlag Rütten and Leoning, Frankfurt am Main), then we first and foremost shrug our shoulders disconcertedly. This is because the name and figure of Georg Brandes alone render the question “Jew or European” paradoxical. Because who other than a Georg Brandes would have been “a good European” in the Nietzschean sense of the word? Hardly another great intellect of the century operated in such a pan-European way as Georg Brandes, who actively exchanged ideas with the great men of his epoch from all nations, and who in response to the impertinent accusation that he was “a Jewish patriot,” or, to put it better, a Jewish nationalist, gave the shameless answer: “Scratch the idiot, and you will find the patriot.” In Georg Brandes, we have always revered one of the most universal intellects of the nineteenth century, who masterfully made his literary and cultural “main currents” accessible to us. And now we read from a close countryman of his, the esteemed Danish writer Henri Nathansen, who has been connected to Brandes for many years, that also the life of this “good European,” which lasted for 85 years, was in its principal elements nothing more than an unending, agonizing, and futile struggle between ancestry and citizenship. Henri Nathansen’s book, a biography, emits sparks of subjectivism and appeals precisely because of its thrilling dynamic. It presents to us a vivid picture of this expert of international literatures, the master of a polished style in many European languages, this passionate disseminator of culture of undisputed worldwide renown. But in addition to this faithful image, Nathansen advances the great confrontation that raged and stormed between the Jew and the European George Brandes for eight decades. As the son of a good Jewish family, without the slightest religious or traditional bonds, born in Copenhagen, Brandes—according to Nathansen—nevertheless felt already as a small boy the opposition of the Danish way of life to the Jewish psyche. He was, like many of his kind, as Nathansen puts it, “handicapped in a certain way from the start.” And with glowing passion, Nathansen chronicles how the indolent and indifferent Jew Brandes denied the Jew at the beginning of his career in himself, didn’t want to hear about a sense of solidarity with the Jewish people, and to his Danish countryman—whose culture and language he shared—reached out his hand one hundred times and felt his hand rebuffed one hundred times. Nathansen describes how the older and more experienced Brandes became, the more he was obligated to learn to think and feel in a new way regarding Judaism. Nathansen writes:

“Like a threatened and excited animal, Brandes shook the bars whenever the crowd pointed to his face and rubbed his nose in his ancestry. His protest became increasingly angry, increasingly wild, and increasingly piercing, such that over the years he spiraled into a state of paranoia that sounded to Jews and non-Jews like the buzzing of rubbish and denial. Until finally toward the end of his life he instinctively felt the nemesis that even the sharpest mind and the most heated will could not prevent. The more sharply and vehemently he distanced himself, the more sharply he underscored his ancestry, and the more fiercely his fellow Danish citizens faced the denier. For the tragic aspect in the fate of a Jew is not to feel intellectually [geistig] homeless, as Brandes expressed it in one essay. The deepest tragedy is that which was allotted to him: to feel spiritually [seelisch] homeless. He withdrew his hand from his Jewish tribesman in order to extend it to his Danish countrymen. But they did not take the hand, which they might have accepted if he had extended it to them openly and honestly as a Jew.”

The great European first, after he had overcome the cosmopolitanism and eclecticism in himself, acknowledged with an open and proud line of sight his sense of self and his common identity with the Jewish nature and Jewish spirit. As a result of this, he should write grandiose books about “the great gamecocks,” Lassalle, Gambetta, Disraeli, and Heinrich Heine, who fought out of a sense of justice, not out of philosemitism for the Captain Alfred Dreyfus and against the ritual murder in Kiev. But he was only finally able to bring himself to an awareness of his Jewishness over the course of long decades filled with persecution, mourning for the stupidity of the masses, and moral conflicts. Nathansen identifies the deeply human tragicomedy that is rooted in the depths of Georg Brandes’s recognition and self-recognition: in the tragicomic blood brotherhood of his work and his being—in the blood alliance of “Sanguinitas and Melancholia”—, as a mixture of contempt and self-contempt, which Brandes himself told about in his tragicomic story of Don Quixote and Hamlet, in the encounter between the “wandering Knight of the Sad Countenance” and the heavy-hearted prince of Denmark, whose profound harmony no one understood.

Through Nathansen, we get to know the wandering Knight who sits down wearily at the edge of the trench and looks back on his homeless, rootless, and peaceless life. Never was he as mad, as his deriders recounted, as when he mistook the windmills that he fought against for wandering knights. And the lance did not shatter on the windmills, but rather on granite—on the stronghold of stupidity. Only very late did the demonic nature of Brandes recognize that he could only find himself in self-development by immersing himself in those royal columns of intellectual heroes, the great, but similarly homeless, rootless, and peaceless, the “born” princes of the grace of God in their terra incognita of the mind, which includes eternity; the Shakespeare, Goethe, Voltaire, Caesar, Michelangelo, who all brought Brandes closer to the European world and the European spirit. Nathansen, who says that Brandes always was and remained an unhappy lover of Denmark, lets him speak for himself:

“The Jews of Western Europe who speak Danish, French, English, and German, have—since becoming equal to the other residents of these countries—generally seen themselves simply as Danes, Frenchmen, Englanders, and Germans. If they hold religious convictions, it didn’t make for a disadvantage for the nationality. My convictions were derived from Spinoza, and Spinoza was not only loathed by the Christians, but also expelled from the synagogue. So it happened that I only felt like a Jew when I was insulted as a Jew, but that of course has happened since the first days of my public appearances. Not a single one of my opponents refrained from recalling my Jewish origins. It was thus impossible for me to forget that I was a Jew, or more accurately, that I would never be regarded as fully Danish, neither in Denmark nor abroad. The word assimilator [Assimilant] did not exist in my youth. I didn’t hear it until I was fifty years old. I emphatically reject being counted among the so-called assimilators. Until my 24th year, I never spoke another language besides Danish; I still today speak no word of Hebrew; I grew up with Danish-national ideas; by nature, I had nothing linguistically or culturally Jewish about me. The ‘assimilation’ couldn’t take anything from me.”

George Brandes denied with the furor of his only too easily exalted soul the existence of a Jewish race and the possibility of a Jewish nation. He might have been right in both cases. And so arose gradually from his renunciation of the only-Jew in himself and, in turn, from the defense of Denmark against it, something bigger, more diverse, more powerful: namely the “European.” But the aging Brandes fared just like Heinrich Heine, who became a renegade due to the necessities of his time, and who wrote from his “mattress grave” his most magnificent book, his “Confessions,” in which he again remembered the God of his fathers and—out of forsworn faith and scorned longing—wove an especially valuable carpet to lay at the feet of the great Unseen who gave the moral law at Sinai. In Brandes, who from his all-encompassing Europeanness in the coming years—possibly also due to growing homelessness and rootlessness—there primarily arose a timid, but then an increasingly impetuous feeling of solidarity with Judaism and an increasingly strong understanding of Jewish endeavors. At the end of his life he wished

“to make a book demonstrating that the New Testament is literature and that Jesus is a fictional character. Not with the intention of stealing anyone’s faith—which would be unfeasible and pointless work—but rather in order to determine scientifically that the Jews could not have crucified a figure who never existed. This superstition invoked the hate and cruelty of the whole world toward an innocent people and rendered it without rights, without peace, and without a home for millennia.”

Georg Brandes was during his lifetime a bit of an Ahasver. Because of this he was able to take the “Family of Denmark” as a starting point for finding his home in Europe, only to find eternal peace within Israel. A great polemicist, an even greater problematizer, at times a pamphleteer, always an insurgent and revolutionary of the purest blood, a fighter for truth and justice: thus, Brandes completed his pilgrimage while separated by the mark of Cain on his forehead. Because, in him, the oppositional was a sensation. And Nathansen might have been right in his fantasy that the contradictory and resistant Jewish character traits of Georg Brandes united to give him the overall impression of the Janus-face derived from Rembrandt’s fused doubleface of Saul and David. Nathansen has answered the question “Jew or European” through the synthesis of the great European Georg Brandes. He gave him two sources of life: Hellas and Judea. In an emotional farewell, he describes his great friend:

“How the light flares before it expires: his nature associated with Judea and his intellect associated with Hellas gather together in one last flickering flame. He sacrifices the last light of his spirit and the last drops of his blood to the gods of Hellas who live easily and the harshly judging gods of Judea—Eros and Ethos, Sanguinitas and Melancholia, the two demonic powers, which have been fighting in his contentious and belligerent disposition for this whole life.”

Such dualism oftentimes festers as a burning wound of Amfortas also in some less brilliant European Jews. But there will always be only one single healing balsam, at least for West European Jews, and it will be called: Europe forever. We live in the diaspora, certainly, but no longer in galut [Golus], no longer in the ghetto. We live as free persons among free nations. Our dreams and longings stroll through the ancient streets of the tribe that wandered in the desert and catch sight of their goals in biblical legends—but our rights and our duties belong to the nations in whose cultural and linguistic communities we were born and raised.

Commentary

Doris Wittner, “Jew or European,” 1930. Commentary by Kerry Wallach

“Jew or European” is one of about 100 feuilletons that journalist Doris Wittner published in the German-language weekly newspaper Jüdisch-liberale Zeitung between 1924 and 1933. It appeared below the line on December 4, 1930. That same month, Wittner also contributed feuilletons about theater critic Julius Bab and writer Franziska Mann (the sister of Magnus Hirschfeld), as well as a front-page article about contemporary analogies to the Book of Job.

Read Full

The Jüdisch-liberale Zeitung (Jewish Liberal Newspaper) was the official organ of the Vereinigung für das liberale Judentum e.V. (Association for Liberal Judaism). Founded in Breslau in 1920 and based in Berlin as of April 1922, the paper gained serious recognition in the mid-1920s. Its circulation reached about 10,000, and Bruno Woyda served as editor-in-chief through March 1931. The Jüdisch-liberale Zeitung originally represented Liberal Jewry in a religious sense but later took a decidedly more political stance as the Nazi threat loomed. It was in fact one of the first German-Jewish periodicals to be destroyed by the Nazis, though it was reincarnated in November 1934 as the Jüdische Allgemeine Zeitung and continued publication through September 1936.

A prolific feuilletonist, novelist, and editor, Doris Wittner (1880–1937) published in both mainstream and Jewish papers. She came from a family of Berlin journalists: her father, Isidor Levy, was an editor of the Berliner Zeitung, and her uncle, Max Albert Klausner, served as political editor of the Berliner Börsen-Courier and later contributed to the Jewish magazine Ost und West. Doris Wittner’s work appeared in major Berlin dailies (Vossische Zeitung and Berliner Tageblatt), literary magazines such as Die Weltbühne, and in periodicals aimed at Jewish readers including the Jüdisch-liberale Zeitung, C.V.-Zeitung, Israelitisches Familienblatt, and Die jüdische Frau. During a career that spanned nearly four decades, she helped shape the genre of the feuilleton by producing a wide range of cultural criticism. Much of her work emphasized the talents of prominent Jewish figures and aimed to advance an awareness of Jewish literature, history, and culture. In 1931, Wittner was also involved in founding and editing a short-lived Jewish journal, Freie jüdische Monatsschau. In this journal and in many of her other articles, Wittner championed Jewish women and their accomplishments. In addition, two of Wittner’s novels were published in serialized installments in the Weimar Jewish press (Der tote Jude in the Jüdisch-liberale Zeitung; and Das Auge Afrikas in the Jüdische Bibliothek supplement of the Israelitisches Familienblatt, both in 1926–27).

The subject of this feuilleton is Danish-Jewish critic Georg Brandes (1842–1927), who lived in Berlin for five years beginning in 1877. A number of his works were translated from Danish into German, and Wittner first wrote about Brandes on the occasion of his visit to Berlin in 1925. This article from December 1930 discusses the German translation of Henri Nathansen’s biography of Brandes, using it as a point of departure to address such broader concerns as antisemitism, Zionism, assimilation, and European Jewish identity.

Further Reading:

- Michael Brenner, The Renaissance of Jewish Culture in Weimar Germany (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1996).

- Margaret T. Edelheim-Muehsam, “The Jewish Press in Germany,” Leo Baeck Institute Year Book 1 (1956): 163-76.

- Herbert Freeden, The Jewish Press in the Third Reich, trans. William Templar (Providence: Berg Publishers, Inc., 1993).

- Henri Nathansen, Jude oder Europäer. Porträt von Georg Brandes (Frankfurt am Main: Rütten and Leoning, 1931).

- Kerry Wallach, “Front-Page Jews: Doris Wittner’s (1880–1937) Berlin Feuilletons,” in Discovering Women’s History: German-Speaking Journalists (1900–1950), ed. Christa Spreizer (Oxford: Peter Lang, 2014), 123–45.