Explore Feuilletons

Converting for Love

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

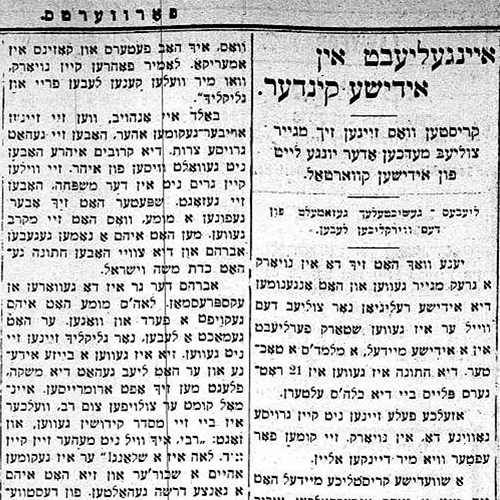

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

URI

Translation of

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Abraham Cahan, “Converting for Love,” 1902. Translated by Louis Kaplan

Subtitle: “Christians who Convert because of Jewish Maidens (medkhens) or Youths from the Jewish Quarter”

Sub-subtitle: “Love Stories Collected From Real Life”

Read Full

This week, here in New York, a Greek converted and took up the Jewish religion just because he fell madly in love with a Jewish girl, a melamed’s daughter1. The wedding was at the home of the bride’s parents, at 21 Rutgers St.

Cases like this are not a novelty here in New York, in fact they happen much more often than we think.

A year and a half ago, a Swedish Christian girl fell in love with a Jewish young man. They worked in the same place, in a sheet metal factory, and he was also hopelessly infatuated with her. They did not know what to do. Finally she reached a decision: she was an orphan, she had no father, no mother, not even any relatives here in America. She was alone in the world, but he lived with his elderly mother and his sister. If he were to convert, his mother would likely not survive it, therefore the Swedish girl decided to take on the Jewish religion.

It did not go smoothly. The Jewish conversion ceremony is not a difficult one for a woman, she goes in the mikveh and that’s enough. But there were other difficulties. At first they deceived his old mother. They told her that the girl was Jewish, but she didn’t know a word of Yiddish! Nu, well, anything is possible. . . there might be some Jewish girls in America that can’t speak Yiddish. But the old woman eventually found out they had deceived her. Once, in the heat of an argument, a neighbor insulted her by accusing her son of marrying a shiksa. This was enough to greatly embitter everyone’s life for a time. The old woman would not stop crying and moaning. But little by little her heart warmed to the pair and she gave her blessing, with the hope that she could transform her daughter-in-law into a frum, kosher Jewish woman.

And her hope was fulfilled. She turned her daughter-in-law into a true tsadeykes. She taught her how to make blessings, light the candles, kasher the meat, go to the mikveh and other essential Jewish laws. In short, the convert became frumer than the frumest Jewish woman. At first the poor girl was all jumbled up and would make simple mistakes. For example, she knew that lighting the candles on Friday night is a mitzve. Nu, so why not do it every day? One time, in the middle of a Wednesday, she lit the candles and blessed them, and her mother-in-law laughed, brimming with joy. The convert lived very well with her mother-in-law (only sometimes when the old woman was angry and had no one to take her anger out on, she would reproach her daughter-in-law for being a shikse).

The convert lived very well with her husband. The two of them were very happy, and the Jewish neighbors who lived with them said that no better life could be found even among a real Jewish couple.

There are many events like this.

The main reason for this is not that New York has such a large Jewish community, but because circumstances are suitable for it. Jews are not as separated from goys here as they are in Russia for example. Jewish girls work together with Christian youths in the same factories, they go to school together, Jews and Christians lead almost the same lives and most speak the same language. They are not so estranged from each other and therefore these mixed marriages happen more frequently.

Naturally, however, not all such matches are happy. Here is another example: He was a Lithuanian Christian from Courland and she was a Jewish girl. They met in Little Russia2 when he was a soldier. Leah—as she was called—was the daughter of a tavern keeper in the city where the soldier was stationed. He was so taken with her that he was happy to convert. However, in Russia, this was not a viable option. Leah said to him: “You know, I have uncles and cousins in America. Let’s go to New York where we can live a free and happy life.”

In the very beginning when they came here they had a lot of trouble. Her relatives didn’t want to associate with her. They told her they didn’t want converts in the family. Later, however, she found an aunt who took them under her wing. He took the name Avrom and the two had a Jewish wedding.

Avrom the convert became an expressman3. Leah’s aunt bought him a horse and wagon. He made a living, but they were not very happy. She was a severe Jewess and he loved his liquor.—They would quarrel often. One time he went to the Rav who married them, and said “Rabbi, I don’t want to be a Jew anymore. Leah is a snake.” He came home drunk and she gave him a whole sermon. Nevertheless, they lived together okay. They had a little baby girl and Avrom the convert loved her as much as life.

Here is another example that shows that, in these matches, it is better not to rush. An Irish youth wanted to marry a Jewish girl. He was a waiter in an uptown restaurant, and she was a cashier there. She had some money set aside and he was a poor man. She was happy to marry him, with the condition that he convert. He agreed, but as time went on and their story was drawn out, the ceremony was delayed from day to day. The girl’s uncle delayed it even further, which turned out to be a blessing for everyone. The pair couldn’t withstand it. If they were truly in love, one can’t really know. Some say that she did not care for him so strongly, but simply wanted an Irishman for a husband. Long story short, the two young people had enough time to find faults in one another. They had time to “go out” with each other, spend nights together, and to fight. At the end, they grew bored of one another, and called off the match.

A Klezmer from Eldridge Street told a comical story about an Italian Barber, a goy, who married a Jewish working girl. The Italian had a barbershop on Broome Street and she lived nearby, with her parents in a tenement house.

When he met her he had already been in the country for five years, and could be found around Jews. He spoke Yiddish with an Italian accent, but very fluently, and he found great favor in the eyes of the girls. He was such a good dancer that he felt above the need for dancing school. His beautiful eyes bewitched the girls, and his basherte4 liked his looks more than anyone; his movements with the hands, with the shoulders, and with the eyes. “He is so sweet when he talks,” she would say, “we Jews can’t possibly flirt so beautifully.”

Other girls would make fun of her love. They didn’t trust “Joe” (as he was called), they didn’t trust his intentions or believe he was serious in his love. She would become annoyed with them, when they rebuked him for being a “goy,” she would get angry and exclaim:

“Nu, so what if he’s a goy. He is a thousand times better than your grooms.”

Several days later Joe went to the girl’s father and said:

“I love Katie. We cannot live without each other. I want to become a Jew and marry her.”

The old man thought that the Italian was making fun of him. But his daughter asked her father for the same thing. The old man brandished a stick and told the Italian to get out of his house. He threatened him, saying that if he had anything more to do with his daughter he would lose all his customers.

Joe left, but came back again and again, and eventually sent a matchmaker to Katie’s father. The matchmaker explained to the father that one shouldn’t play with love; If he would not allow his daughter to marry the Italian, she would elope with him and become a goy.

He had to give in.

The Italian converted and married Katie and they lived together like doves. But a few weeks after the wedding she got sick, and when she finally arose from bed she had become frum. She greatly embittered Joe’s life. She hired a melamed for him, so that he would learn to daven, and she wanted him to do nothing less than daven three times a day.

“I got sick because of you. And if you don’t become frum, I’ll get sick again. And our children will die from it!”

Poor youth! He did everything in his power to make her happy. And she had become so frum, that it was never enough. He would often ask her:

“You see how other Jews we know conduct themselves. Do they pray? Why must I be a better, more kosher Jew than them?”

She told him that since they were born Jews, they could do as they wish. But he was a convert, so he must follow all the Jewish commandments.

So he laid tefillin every day. However, often, when she would go out on the street in the morning to buy something, he would wait until she came back, and when he saw her through the window he would go put on the tefillin and mumble a bit so that she would think he had been praying.

Aside from this, they lived a good, happy life.

- Some words from the source text in Yiddish and Hebrew have been left in LOTE. They have not been italicized so as not to foreignize the source text and culture from the translation. ↩

- In the Yiddish, ‘Kleyn Rusland’, most likely meaning the region now called Ukraine. ↩

- A person who makes collections or deliveries for an express company (Dictionary.com). ↩

- Destined one, meant to be. ↩

Commentary

Abraham Cahan, “Converting for Love,” 1902. Commentary by Ayelet Brinn

In March of 1902, journalist and socialist agitator Abraham Cahan returned as editor of the New-York-based socialist Yiddish daily Forverts (Forward) after a five-year hiatus. Cahan had been one of the newspaper’s founders in 1897 and its first editor-in-chief, but had resigned after not receiving full creative control. In the interim, Cahan wrote instead for English-language newspapers like the New York Commercial Advertiser and the New York Sun. Unlike the Forverts, these newspapers were not politically radical, nor did they speak to an audience primarily composed of Eastern European Jewish immigrants. In these publications, Cahan mainly wrote a genre of features called “urban sketches,” describing life in New York’s immigrant neighborhoods to the newspaper’s readers. Urban sketches were a common theme for features in American mainstream newspapers in this period, but were also a classic theme for feuilletons in various countries going back to the second half of the nineteenth century. When he described this phase of his career in retrospect, Cahan switched back and forth between calling these articles “features” and “feuilletons”—highlighting his engagement with American and transnational journalistic trends (Cahan, vol. 4: 276-9).

Read Full

When he returned to the Forverts, one of Cahan’s goals was to transform the paper so that it conformed to the lessons he had learned while working for English-language newspapers. Up to this point, Cahan felt that the Forverts’s content had been dry and its audience relatively small. Cahan wanted to bring both mass appeal and human interest to the paper by including features and feuilletons, articles that were meant to entertain readers as much as inform them. In order to achieve this aim, Cahan translated several of his recent articles for English-language newspapers and adapted them for inclusion in the Forverts. In Cahan’s mind, these articles could serve as a bridge between the English- and Yiddish-language press (Cahan, vol. 4: 276-9).

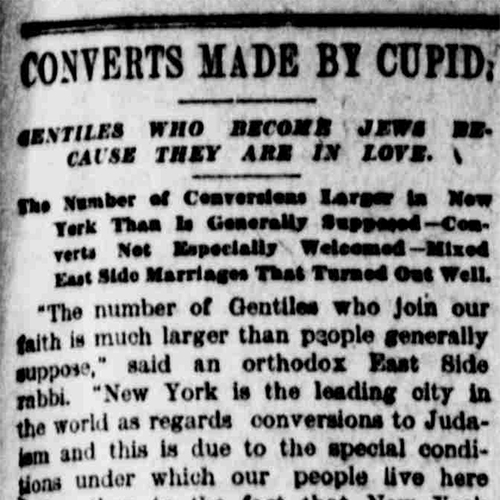

One of these adapted articles, “Converting for Love,” appeared in the Forverts on March 16, 1902. Cahan discussed non-Jews living on New York’s Lower East Side who converted to Judaism after falling in love with Jewish neighbors or acquaintances. Most of the article focused on the complications these couples faced when attempting to build lives together. In some cases, Cahan highlighted the humor of these complications—focusing, for example, on a Swedish woman’s attempts to learn the details of Jewish rituals. In other cases, Cahan focused on how the authenticity of these converts was continually questioned by their new families—making it difficult for them to ever feel fully accepted. Cahan had previously published an English-language version of this article anonymously in The Sun on July 21, 1901 under the title “Converts Made by Cupid.” In order to update the article, and to make the text fit with its new setting, Cahan made several changes, including adding a summary of a recent local news story about a Greek immigrant who converted to Judaism in order to marry the daughter of a prominent scholar.

Therefore both the article itself and the context in which it was produced speak to the permeable, complicated boundaries surrounding American Jewish immigrant communities at the turn of the twentieth century. By focusing on stories in which Jews and non-Jews met and fell in love, Cahan evoked the multi-ethnic neighborhoods in which many Jews lived when they first arrived in America. Intermarriage rates between Jews and non-Jews were quite low in this period, though some Jewish communal leaders were still afraid that these numbers might increase at any moment. Cahan therefore picked up on a theme that would have interested readers of both Yiddish and English-language newspapers, whether because they identified with the subjects of the article or because they were curious about lives different from their own. At the same time, the fact that Cahan adapted this article from his own English-language writing demonstrates the intertwined development of American Yiddish and English newspapers, and the ways in which journalists like Cahan attempted to bring these spheres into closer conversation.

Further Reading:

- Abraham Cahan, Bleter fun mayn leben (New York: Forverts Association, 1926-31) 4: 276-9.

- Abraham Cahan, Grandma Never Lived in America: The New Journalism of Abraham Cahan, ed. Moses Rischin (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1985).

- Jessica Kirzane, “Ambivalent Attitudes Toward Intermarriage in the Forverts, 1905-1920,” Journal of Jewish Identities 8, no. 1 (2015): 23-47.

- Keren R. McGinity, Still Jewish: A History of Women and Intermarriage in America (New York: New York University Press, 2009).