Explore Feuilletons

A Bundle of Tkhines

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Yankev Azriel Davidzon, “A Bundle of Tkhines,” 1911. Translated by Veronica Belling

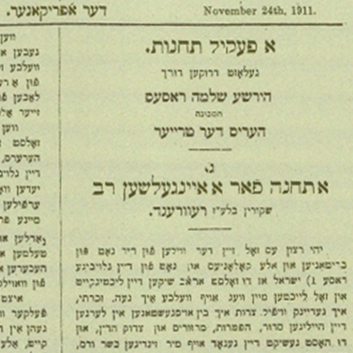

A Bundle of Tkhines printed by Hirshe Shloyme Rases (ראססעס) also known as Harris the Tryer

A Tekhina for an English Rov Called in Loshn La’az a “Reverend”

Read Full

May it be Thy Will, Oh God of Britannia and of all the colonies and of Thy chosen race Israel that Thou should send down Thy light to illuminate my way. I remember how I suffered learning Thy holy siddur, hafteyrahs, makhzeyrim, and funeral rites, and Thou had mercy on me, sinful flesh and blood, whose sins were red as crimson, as it is written in Thine holy hafteyrah, “Be your sins like crimson” and Thou made them white as snow. “They can turn snow white.”1 And I remember how I panicked when I took the examination. God forbid my tongue should stumble, but Thou, the all powerful, had mercy on me and gave me a white collar, to demonstrate that my sins had become white. And in the examination Thou gave me such a swift tongue, as fast as the horses at the Derby, the pride of Thy blessed people England. I beg Thee, Thou should extend Thy mercy and not abandon me.

When I go as Thine emissary to a funeral or to visit the sick, let the house be free of sick or dead people, let it be healthy and strong, to carry out Thy work, as it is written in Thine holy book, “Build Thy house as in days gone by.” Thine house should be healthy as in former days, healthy and strong, so that I should find favor with them and with everybody, so that they should invite me to picnics, parties, or wherever they play, sing, dance, play bridge, nothing else but bridge, the game of Thy holy people England, not “Sixty Six,” or what interests the members of the associations.

When I go up onto the bima to daven, and when I give a sermon, please keep the Russian Jews, who are not civilized enough to understand the mission of a Reverend, far from me. I remember how they used to mock and laugh at me, Thy servant, because I know nothing of the ancient book that they call “The Talmud.”

When I have to give sermon, as when there is a sermon in a church, please would you give the listeners a sense of propriety, both Thy blessed people, England, and Thy Chosen People, Israel, so that they should applaud my every word, so that I should be regarded as one who fulfills the “Mission of Israel.” Send some sense to my synagogue leaders and gaboyim so that they should put away their needles and their machines and come to hear how gentlemen applaud Thy servant, so that they should increase my wages. I should be able to serve Thy name with goodness.

On behalf of all the nations of the world, I wish that they should all walk in the ways of truth and beauty and sincerity in the ways of Thy blessed people, England. Let the sport of horses and dogs, boxing and cricket, golf, tennis, football, and all other precious gifts that Thou hast bestowed upon Thy blessed people, England, flourish among them. Send them good sense so that they should not encourage Thy Jews, who study their book that they call “The Talmud,” to come to the blessed land of England and make a figure of fun of reverends. And if they should come, send them the spirit of civilization, so that they should forget their Talmud, and walk in our ways. And I hope that you will fulfill the request of my lips and my eyes shall witness the return to Zion. Amen.

1) We don’t say the “folk” Israel, God forbid we should make enemies of the gentlemen, our brothers, the English “folk.”

2) One should pronounce the “ז” from Zion so as not replace it with a “צ” in error and make it seem that we actually mean emigration to “Tzion.”

- 1 Isaiah 1:18. ↩

Commentary

Yankev Azriel Davidzon, “A Bundle of Tkhines,” 1911. Commentary by Eli Rosenblatt

A pioneer of Yiddish journalism in Southern Africa, Davidzon would pen tkhines, parodies of supplicatory prayers written in the Yiddish vernacular, for various South African Jewish “types,” including teachers, ritual slaughterers, familiar wagon drivers, peddlers, bathhouse attendants, and urchins of all sorts. Part of this series of tkhines, the text is a prayer for an “English Rov,”a rabbi that through geographic origin, education, or inclination had taken on the aesthetic and ideological positions of a non-Orthodox British-Jewish intellectual. In mocking this type of rabbi’s ignorance of ancient rabbinic texts and his contempt for the “primitive” rituals of recent Yiddish-speaking immigrants, Davidson gives a stark sense of his distaste for the arbitrary and false divide between “civilization” and “barbarism” that ran through the South African Jewish community, and colonial South African society at large.

Read Full

As Joseph Sherman suggested, the racialization of a Yiddish linguistic dichotomy between “Us” and “Them” shaped how Lithuanian Jews in South Africa expressed themselves in colonial society. The environment shaped the ways in which Davidson engaged the traditional Jewish texts he sought to reclaim for modern literature. In turn, he introduced the feuilleton form to colonial African society and asserted African Jewish communities as legitimate sites for generating modern Yiddish literature.

Southern Africa, a region consisting of different races, cultural identities, languages and ethnic bonds, has harbored an Ashkenazic Jewish community since the early nineteenth century. In 1795, when the British took control of the Cape of Good Hope, they continued the Dutch policy of racial segregation. Ashkenazic Jewish immigrants, this time from Prussia, joined the British colonial economy as a direct result of their emancipation in 1812. These first arrivals, mostly from England and Germany, established communal organizations on the British model. After 1880, another more numerous migration of predominantly Lithuanian, Yiddish-speaking Jews arrived in South Africa, another branch of the same mass migration that would bring hundreds of thousands of Jews to North and South America. The Yiddish press in South Africa was established by Nehemia Dov Hoffmann, who arrived in Cape Town in 1889 from the Kovno region. Davidson belonged to a generation of Yiddish journalists working in Hoffmann’s shadow, recording the development of a new Jewish culture in the shadow of colonial settlement and violence.

Further Reading:

- Davidson, Yakov Azriel, Veronica Belling, and Mendel Kaplan. 2009. Yakov Azriel Davidson: his writings in the Yiddish newspaper, Der Afrikaner, 1911-1913. Cape Town: Isaac and Jessie Kaplan [Centre] for Jewish Studies and Research, University of Cape Town.