From the early decades of the nineteenth century, the feuilleton was one of the most popular and most controversial forms of writing in newspapers throughout the world. The French word feuilleton is a diminutive of feuillet (“leaf” or “page”); hence, feuilleton means “small leaf,” in reference to its mode of inclusion in newspapers. At first, the feuilleton was a sheet added to the newspaper, with a variety of short articles and announcements on events in Paris around the time of the French Revolution. In 1800, instead of being a detachable addition to the newspaper, the feuilleton became part of it, yet still visibly marked as different by a line. This demarcation happened on the pages of the Parisian paper Journal des débats, where it quickly became evident that the feuilleton had the potential to transform the newspaper industry. Readers would buy the paper to read the latest installments of the feuilleton every day or every week.

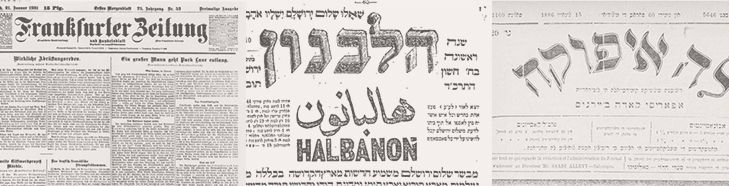

Within a few decades, the feuilleton had spread across Europe and beyond, rapidly establishing itself as the urban genre of the new mass-oriented press and wildly popular with the emerging educated bourgeoisie—Jews included. While it accelerated the proliferation of the popular press in major cities and was a key space for the expansion of the “public sphere,” it also helped establish a uniquely Jewish public sphere in the press over the course of the nineteenth century. The feuilletons’ place in the space en rez-de-chaussée (“ground-floor level”) or unter dem Strich (“below the line”) indicated that feuilletons could be cut off and read separately, independent from the rest of the paper and the political news that were subject to censorship. By 1900, the feuilleton had become a site for literary and polemical performances in the newspaper, featuring wide ranging topics: cultural and political criticism, articles of literary and scientific nature, as well as stories, sketches, travel accounts, local reportage, and poetry.

The feuilleton intersects with Jews and modern Jewish cultures in a number of intriguing ways. Many Jewish writers, journalists, and political figures wrote feuilletons, often side by side with literary, philosophical, and political works. As a result, over the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the feuilleton became associated — both in Jewish and antisemitic discourses — with Jews and Jewishness and was understood by some to be a “Jewish” genre or form. Feuilletons were written by Jewish writers in both Jewish and non-Jewish languages. Importantly, the feuilleton was an important feature in the creation of a transnational modern Jewish press as well as an important vehicle for Jews to partake in national cultures across Europe, such as in France and Germany.

Feuilletons were multilingual, transnational, and published in a remarkable number of languages across the globe. By the early twentieth century, the feuilleton was a key site for discussions of national character, portraits of urban life, and cultural innovation and aesthetic experimentation. While the feuilleton is an historical phenomenon, its role in shaping modern Jewish cultures and a Jewish public sphere raises questions about changing modes of cultural communication, the distinction between news and commentary in mass media, and the formation of both Jewish cultural discourse and secular political discourse. These issues are all the more relevant since the advent of digital media and the digital age.