Explore Feuilletons

Uncle Ezra and His Wife Benuta

Item sets

Abstract

Title (English)

Title (original)

Title (transliterated)

Date Issued

Place issued

Author

Newspaper

Language

Content type

Translator

Contributor

Copyright status

Related Text

Keywords

Original Text

Translation

Moshe Cazes, “Uncle Ezra and his Wife Benuta,”1 1939. Translated by Marina Mayorski

- Ezra:

I will tell of wisdom, Sweet for all creations, I will raise turrets, To set the passersby aright…!2

- Benuta: Ezra, drink the coffee. Why did you get me up on my feet like a pheasant? - Ezra: So that you hear the Law a little bit. - Benuta: Wasn’t reading the entire night at the meldado3 enough for you? - Ezra: What I read at night in the meldado is not called Azarod (Azharot)4. And if I’m reading it to you, it is for you to understand the greatness of this holiday.5 - Benuta: What can I understand when you’re reading in Arabic. What is the meaning of, “I will tell of wisdom, sweet for all creations, I will raise turrets, to set the passersby aright”? - Ezra: Do you see why I tell you that you don’t even have a small amount of Judaism left in you. Remember when you got mad at me for reading a pasuk at the table? Now you have woken up all of the cucumber vendors. You don’t know what is the meaning of “I will tell the benignancy of Him Who Shall Not be Named,” which is sweet for all that is created in this world. We need to climb the turrets of the walls or on the White Tower, to tell it to all the passersby.6 - Benuta: That’s what it means? - Ezra: Yes. - Benuta: And for that you started screaming at seven in the damn morning to wake up the whole neighborhood? - Ezra: Yes, so that they hear the wonders of these words:

I extricated you, I forewarned you, I guided you, In righteous paths.7

- Benuta: Ezra dearest, the people are asleep. I didn’t live in this world nor come to it, what business do you think I have with the whole world now? Don’t you know that we are no longer uncouth common folk like potters at the market? Do you think we’re living in the town square now? - Ezra: Wherever we may live, there God blessed He be we will see us and will listen to us. […]

- Bunis, Voices from Jewish Salonika, 437–8 (no. 36). Trans. Marina Mayorski. ↩

- Translated from the Ladino version of the Azharot. Hebrew original: אספר תושיות / מתוקות לפיות / ואציב תלפיות / לישר העוברים. For an English translation of the Hebrew original, see: Rabbi Shimon Ben Zemach Duran, Zohar Harakia, trans. Philip J. Caplan (Lanham MD, 2012). ↩

- The Meldado is the study group or forum for religious Jewish learning in the Sepahrdi world. See: Matthias B. Lehman, Ladino Rabbinic Literature and Ottoman Sephardic Culture (Bloomington IN, 2005), 78–84. ↩

- Azharot is one of only two known long poems by Ibn Gabirol, a versification of the 613 precepts that comprise the Jewish law, presumably written in his early youth. Ezra originally sang the Azharot in Ladino, probably using an eighteenth-century translation that had since become outdated; this explains why Benuta was unable to understand their content. ↩

- Shavuot. ↩

- Salonika’s White Tower, known in Ladino as Beáz Kulé (from Turkish) or Kuli Blanka, is a well-known city landmark residing on its waterfront. It was constructed after the Ottoman capture of the city in 1430, replacing an older Byzantine fortification. ↩

- Hebrew original: אני הוצאתיך / אני היזהרתיך / אני הידרכתיך / בדרכי מישרים. ↩

Commentary

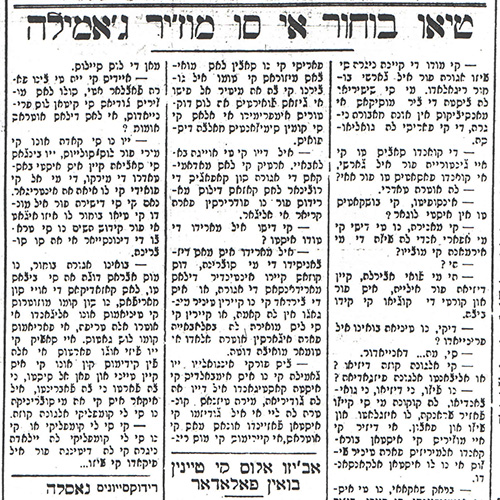

Moshe Cazes, “Uncle Bohor and His Wife Djamila” and “Uncle Ezra and His Wife Benuta,” 1939. Commentary by Tamir Karkason

These two satirical feuilletons were written by Moshe Cazes (1889/90–1942/3) of Salonica in the late 1930s. The feuilletons, collected and published by David Bunis (1999), feature the fictional characters Uncle Ezra (or Bohor) and his wife Benuta (or Djamila) and reflect life in Jewish Salonica. Since several thousand people bought copies of newspapers Aksyon (An Action, 1929–1940) and Mesajero (A Messenger, 1935–1941) each day, the heroes of Cazes’s pieces must have been the talk of the day in Jewish Salonica at the time.

Read Full

In 1912, Greece conquered the Ottoman city of Salonica, which was home to some 80,000 Jews. During the period of Greek rule, the texture of Jewish life in Salonica changed dramatically; from one of many ethnic groups in the Ottoman state, the Jews became a small national minority in the Greek state. The Salonican Jews, who had constituted a majority in the city during the Ottoman period, were forced to cope with laws and regulations initiated by the state that sought to strengthen the Hellenic character of the country. The life of the Jews in Greece was not entirely negative, and Hellenization also brought a remarkable flourishing of Greek-Jewish culture, but in the final analysis, the years of Greek rule were certainly complex for the Jews of Salonica (Naar 2016).

Following the Greek occupation of 1912, three intellectual and social groups dominated Jewish life in Salonica: The Socialists, the Zionists, and a group identified with Westernization and Hellenization (Naar 2016, 23–24). But there were also Salonican Jews who avoided politics and ideology, maintained religious observance, and were familiar with the traditional literature in Ladino. Fortunately, we have evidence from the last possible historical moment in the form of the satirical feuilletons written by Cazes on the eve of World War II.

Cazes was himself the son of a lower-class religious family, who had both a religious and a modern education, and was also a popular singer as part of a duo called Sadik and Gazoz. Cazes’s satirical articles, which emphasized the tension between traditional Jews and Westernizers, provide a window into the lives of the ordinary Jews who are absent from almost all the other sources. The feuilletons mock the older generation of Jews, those born between the 1860s and 1880s, while ironically identifying with their inability to cope with the changes of the late 1930s.

In the first piece, Ezra, a consumer of Ladino religious literature, read aloud on the holiday of Shavuot the Azharot (Exhortations) of Ibn Gabirol, translated into Ladino in 1742. But his illiterate wife, Benuta, assumes that the language he was reading was not Ladino at all, and certainly not the spoken Ladino the couple used, but rather Arabic – the language of the closest “other” in the post-Ottoman society. Cazes’s satire mocks both the male figure, who is portrayed as overly devout in his religion and practices in a world of increasing secularism, and the female one, for whom an archaic component of her mother tongue seems completely foreign. Almost thirty years into the era of the Greek state, the archaic Ladino that Benuta mistakenly perceives as Arabic brings her back to the bygone Ottoman world from which she – no less than her husband – has been unable to completely disengage.

The processes of modernization and secularization are even more evident in the second piece, where Djamila informs her husband Bohor – similarly, a new name for Ezra – that her niece has chosen to have an abortion. While Djamila has replaced Benuta and Bohor has replaced Ezra in this feuilleton, Cazes’s style and plot are nearly identical to the previous example. Bohor was shocked at the news, as a religious Jew who had never encountered the concept of family planning; as for Djamila, she was not shocked by the abortion itself, but felt sorry for infertile women. This piece illustrates that although Djamila and others like her were raised in conservative homes and rarely left their confines, they were more open-minded and liberal than their male counterparts and displayed an impressive measure of agency as women.

Unfortunately, Cazes and Salonican Jews like Ezra, Benuta, Djamila, and Bohor would suffer a bitter fate just a few years later, when the Jewish community of Salonica and its unique and irreverent culture were annihilated during the Hollocaust. May their inclusion in the feuilleton project help perpetuate their memory.

Further Reading:

- David M. Bunis, Voices from Jewish Salonika: Selections from the Judezmo Satirical Series Tio Ezrá i su mujer Benuta and Tio Bohor i su mujer Djamila (Jerusalem and Thessaloniki: Misgav Yerushalayim, the National Authority for Ladino Culture, and Ets Ahaim Foundation of Thessaloniki, 1999).

- Devin E. Naar, Jewish Salonica: Between the Ottoman Empire and Modern Greece (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2016).